The Hero's Journey

In 1988, “Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth,” a PBS documentary series comprised of interviews between Campbell and journalist Bill Moyers, skyrocketed Campbell’s writings on comparative mythology into mainstream consciousness. At the time I was in my late teens and got hooked on Campbell’s ideas, particularly the archetype of the Hero’s Journey. In college I wrote several papers using the simple, circular/spiral outline created by Campbell to describe the stages of this journey to deconstruct and explicate everything from literary character arcs to psychological principles to artistic themes in the visual arts.

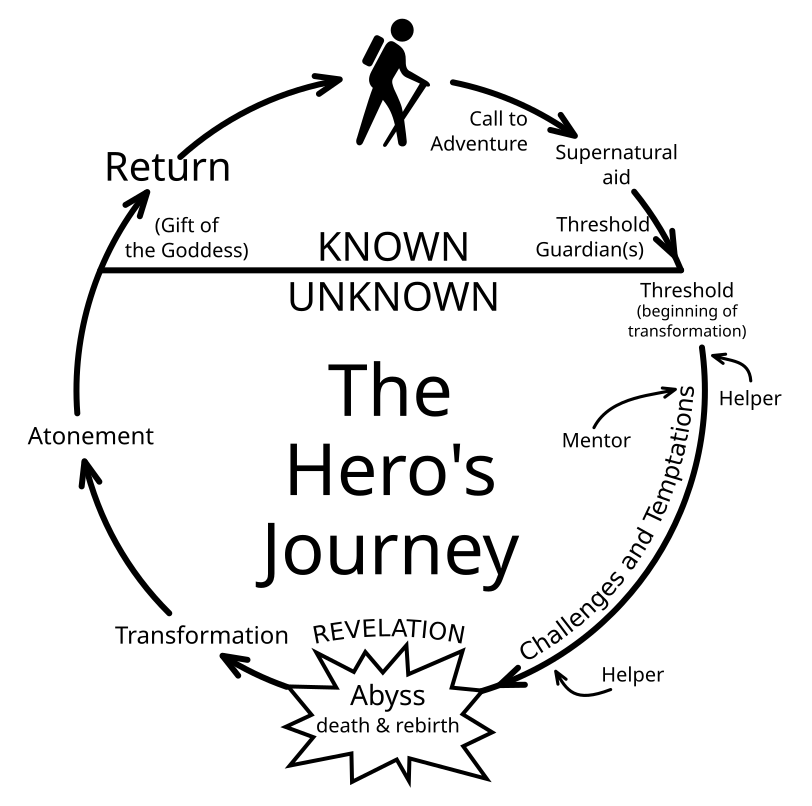

In the archetypal hero’s journey, the hero is summoned to an adventure of some type. The hero may happily and naively leave a happy home and stable community in full confidence of seeking and finding their fortune, or, more often, the hero is thrust out of their home by tragedy or having a fateful task fall to them, (for example, Frodo’s responsibility for destroying the one ring in Lord of the Rings). At some point the hero crosses a “threshold,” a point beyond which they are in the unknown and after which they cannot return to the one they were or the place they were before.

Throughout the journey there will be challenges that must be successfully met in order to continue, as well as temptations that attempt to pull the hero off the path and get lost. There will be helpers, teachers, and devils. At the nadir, where the hero seems to “hit bottom,” there is, if all goes well, a death and rebirth. Although this death and resurrection are metaphorical, in stories and myths they can be described as literal events.

Transformation, integration, and a return to the original world and community eventually follow as the hero returns from the “underworld” or “otherworld” of their journey. Because of the transformative nature of the journey, the hero always returns with a boon—having completed a salvific task they have performed to save the world and/or bearing a unique gift to share with the world they left.

It was not lost on me that the fascinating journey being described belonged to a hero, not a heroine. But in addition to being excited and enchanted by the possibilities and adventure inherent in the hero’s journey, the archetype rang true for me. I was confident it belonged to me as much as to any boy or man. I’m not sure Campbell felt or understood it the same way.

I recently read an essay by Soledad Marambio, a Chilean poet and scholar, entitled, “’The Hero’s Bloody Journey’: What Female Characters Encounter in Menopausal Narratives.” In it she tells the story of a student who was in one of Campbell’s classes when he taught at Sarah Lawrence College, at that time an all-female institution. The student went to Campbell’s office one day and told him that “she was tired of hearing about men. She wanted to hear about women.” Campbell’s response?

“’The woman’s the mother of the hero; she is the goal of the hero’s achieving; she is the protectress of the hero…What else do you want?’”

To which the student replied: “I want to be the hero.” (p.4)

There’s no follow up about how Campbell responded to this, but I suspect that he was not entirely sympathetic. Indeed, Maureen Murdock, an American psychotherapist who studied Joseph Campbell’s work and ultimately created a model of “The Heroine’s Journey,” interviewed Campbell in 1981 and asked him about the hero’s journey for women. He responded, “Women don’t need to make the journey. In the whole mythological tradition the woman is there. All she has to do is to realize that she’s the place that people are trying to get to.”

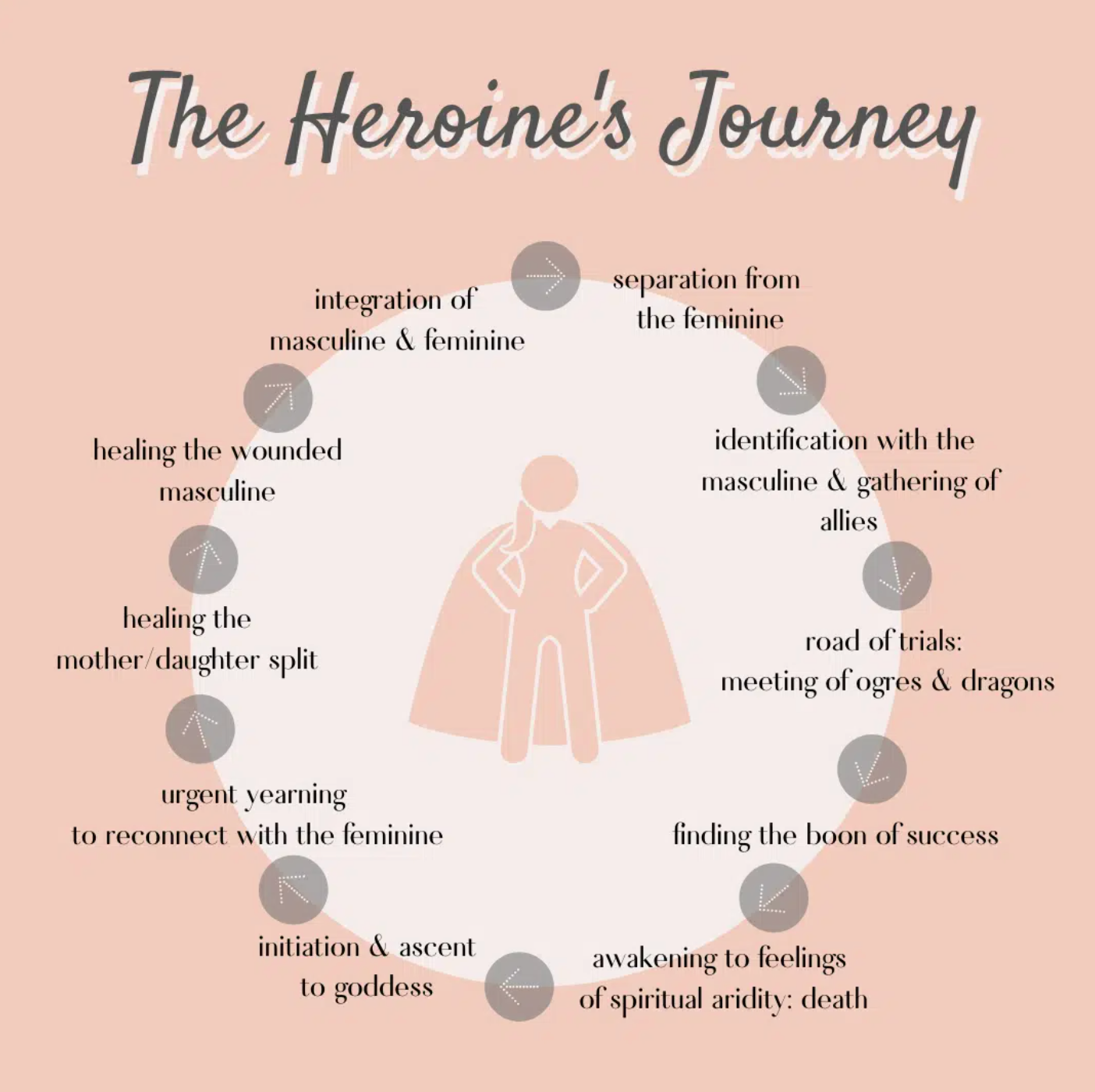

My opinion is that this is straight up sexism masquerading as scholarship. Clearly, women do have physically-based (embodied), psychospiritual journeys to make. Murdock’s model starts with the separation of women from a feminine that has been devalued and debased in patriarchal societies, and their alliance and identification with masculine and patriarchal values in order to survive and thrive. In this model the journey is specifically about healing the heroine’s split from the divine feminine, healing the individual’s mother/daughter wound, and skillfully integrating masculine and feminine energies.

I’m intrigued by Murdock’s model and intend to spend more time with it, but the truth as I see it is that either model could apply to a person of any gender. Men, too, have been separated from the feminine at a high cost and desperately need a reconciliation with the goddess and healing of the “mother wound.” Similarly, in Campbell’s model “marriage with the goddess” is an event that can be undertaken by a hero of any gender, whether this marriage is understood to be literal or metaphorical.

There is, however, one fundamental way in which women and men differ: Women have built-in, physiological “calls to adventure” that men do not.

Although menarche, pregnancy/childbearing, and menopause have not traditionally been considered “adventures,” “journeys,” or “heroic” by most humans, they are, nevertheless, pivotal, life-changing, and even heroic events. “Getting” one’s period, “getting” pregnant, “getting” old, these are things that are spoken about and viewed as passive, as something that happens to someone and over which they have very little control. The language that has historically been used to describe women’s experiences makes it difficult for us to grasp and appreciate the magnitude of these powerful rites of passage.

But if we are inclined to bring consciousness to these life-transforming transitions, we can easily begin to see how our first period, first child, or first symptoms of perimenopause can be a call to adventure. We don’t have to heed this call. We can attempt to maintain the status quo, hold onto our old bodies, our ideas about how all of this is supposed to play out, our beliefs about who we are and what’s true.

Ultimately, if we are to grow, we are eventually thrust across a threshold (some more willingly than others). We descend into doubt, confusion, and chaos as we are separated from what has been familiar to us. Along the way we find allies and battle enemies. At some point, things get dark, sometimes unbearably so. And then, a thin line of light limns the eastern horizon. We breathe again. Gathering strength in a new body, we are reconciled to our losses, and we begin to count our gains. We return to a new way of being in a world that is changed because of our change.

Part of my work in coming to terms with “The Change” of menopause has been to attempt to relate with it

· actively, rather than passively, so that I do not feel victimized by something out of my control that is happening to me

and

· positively, so that all the physical and psychological discomfort and challenge of this transition is given meaning, rooted in a context of transformation instead of deterioration.

In her essay, Marambio explores two autobiographies and two novels that have as their subject matter menopause and mid-life. She views them through the lens of the hero’s journey, which is comprised of three major stages:

· “departure from the familiar daily world,

· initiation in a new, challenging world, and

· return to the former world with the gains obtained during the initiation.”

Marambio posits that “The daily known world of the [women in the books] is shaped by their pre-menopause lives and bodies. Menopause can be viewed as the ‘other world’ where the heroine’s initiation takes place.” (p.1, italics mine)

Campbell has written that the “announcer of the adventure ‘is often dark, loathly, or terrifying, judged evil by the world; yet if one would follow, the way will be opened through the walls of day into the dark where the jewels glow.’” (p.10) Each of the women and characters examined by Marambio are similar in that their life conflicts and crises are being triggered by profound physical, relational, and/or psychological discomfort:

“When I was around fifty and my life was supposed to be slowing down, becoming more stable and predictable, life became faster, unstable, unpredictable.” (Levy in Marambio, p.11)

“Whatever she was—the sum of fifty-three years on the earth in this body—was insufficient to what would come next. She clearly had to change.” (Spiotta in Marambio, p.15)

In attempting to navigate these discomforts they start forth on the path of the hero’s journey. In doing so, they confront demons:

“With every flash, my psyche is pushed to grasp what it does not want to let itself know: that it is not immortal.” (Steinke in Marambio, p.14)

And meet allies:

“Now I was realizing that nature was not full of divinity…Nature itself was divinity…” (Steinke in Marambio, p.20)

In Campbell’s description of the hero’s journey, the hero often marries or mates with the goddess. This unification of the questing masculine with the contextual, gifting feminine is essential to the successful completion of the journey and the integration of the hero’s experiences with [his] self. It makes sense that this peaceable commingling of masculine and feminine energies is an inherent part of this journey of transformation and Murdock includes it as the final step of the heroine’s journey.

Interestingly, what Marambio found is that women most often “married” other creatures/beings. Steinke visited Seattle to visit a pod of orcas after reading that they are one of the only other creatures besides humans to experience menopause. There, she bonded powerfully with Granny, a postmenopausal leader of her pod. She writes, “..what if the postmenopausal narrative, like the prepubescent one, is focused not on romance, but on a creature?...I am not interested in girl meets boy, but in woman meets whale.” (Steinke in Marambio, p.24)

At the age of 52, English artist Tracey Emin married a stone:

“the woman whose life is her art has revealed that last summer she married a venerable stone that stands in her garden in France. ‘Somewhere on a hill facing the sea, there is a very beautiful ancient stone, and it’s not going anywhere,’ she has said. ‘It will be there, waiting for me.’ In another interview she has called it ‘an anchor, something I can identify with. She wore her father’s funeral shroud as a wedding dress.” (Jones, 2016).

[There is a fascinating discussion that could be had here: Why do women not need to marry a god to integrate the masculine? What are women unifying with? Is this type of behavior why Campbell could not see the point of women making the hero’s journey?]

While on the surface these types of alliances may seem odd or even ridiculous, if you dive beneath the surface of things—as these women have done through the process of trying to get through the agitation, grief, and displacement of mid-life and menopause—you may discover that these new types of relating and relationships begin to make sense, especially if viewed through a mythological lens.

Mythology and poetry offer us ways to shapeshift, to walk the margins and take our own paths toward truths yet to be discovered about the worlds we inhabit and that inhabit us. Through them we are freed from a utilitarian, but surface world of literal meaning and empirical fact and permitted to drop into deeper layers of consciousness that express themselves through metaphor and symbolism.

I found the women in Marambio’s essay good company and guides as I start to consider my own menopausal transition as a heroine’s journey. I have begun to chart the call, the crossing of the threshold. I am making a list of my allies, the challenges I have overcome and the new tools I have forged in the overcoming. I am not sure exactly where in the cycle I am, but I suspect I have been negotiating the nadir for several months. At some point soon I will emerge from the depths of this descent, putting one foot in front of the other in a body and mind transformed by my experiences so far. I’m not sure what the road back to the surface looks like or what I will look like as I re-emerge into the light. I don’t know what I will be carrying with me or what will be incumbent upon me to share.

What I do know is that getting in touch with the larger context of my larger self has been both grounding and inspiring. Learning to relate with my personal menopause transition as more than a collection of nagging, unpleasant symptoms that seem to be harbingers of nothing but death and disease transforms them. The harpies stop shrieking and start singing, the banshee begins to prophesy life, and I become someone with a bright future ahead of her.

Katha Pollitt, an American poet and essayist, is quoted in Steinke as writing, “Questing is what makes a woman the hero of her own life.” From this point of view, we are lucky to be women. We are fortunate to have these periodic, physiologically-timed upheavals that uproot us from the routine familiar and offer us the opportunity to travel the road of heroic transformation.

References

Brown, Mark. (2012, May 25). The Saturday Interview: Tracey Emin. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/may/26/tracey-emin-saturday-interview

Jones, Jonathan. (2016, March 22). Stoned love: why Tracey Emin married a rock. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2016/mar/22/tracey-emin-married-rock-love-intimacy

Marambio, S. “The Hero’s Bloody Journey”: What Female Characters Encounter in Menopausal Narratives. Age, Culture, Humanities: An InterdisciplinaryJournal, 7.

file:///Users/Jenny/Downloads/Marambio+ACH+proof+v3.pdf

Revilla, Analyn. (2012, March 15). “The Heroine’s Journey” Is Not One Woman’s Journey. Los Angeles Female Playwrights Initiative. https://lafpi.com/2012/03/the-heroines-journey-is-not-one-womans-journey/

Images:

The Hero’s Journey: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Heroesjourney.svg

The Heroine’s Journey: https://storygrid.com/heroines-journey/

Standing Stone: https://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/382/bordastubble-stones