Biology is not destiny, part 2: Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP)

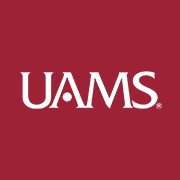

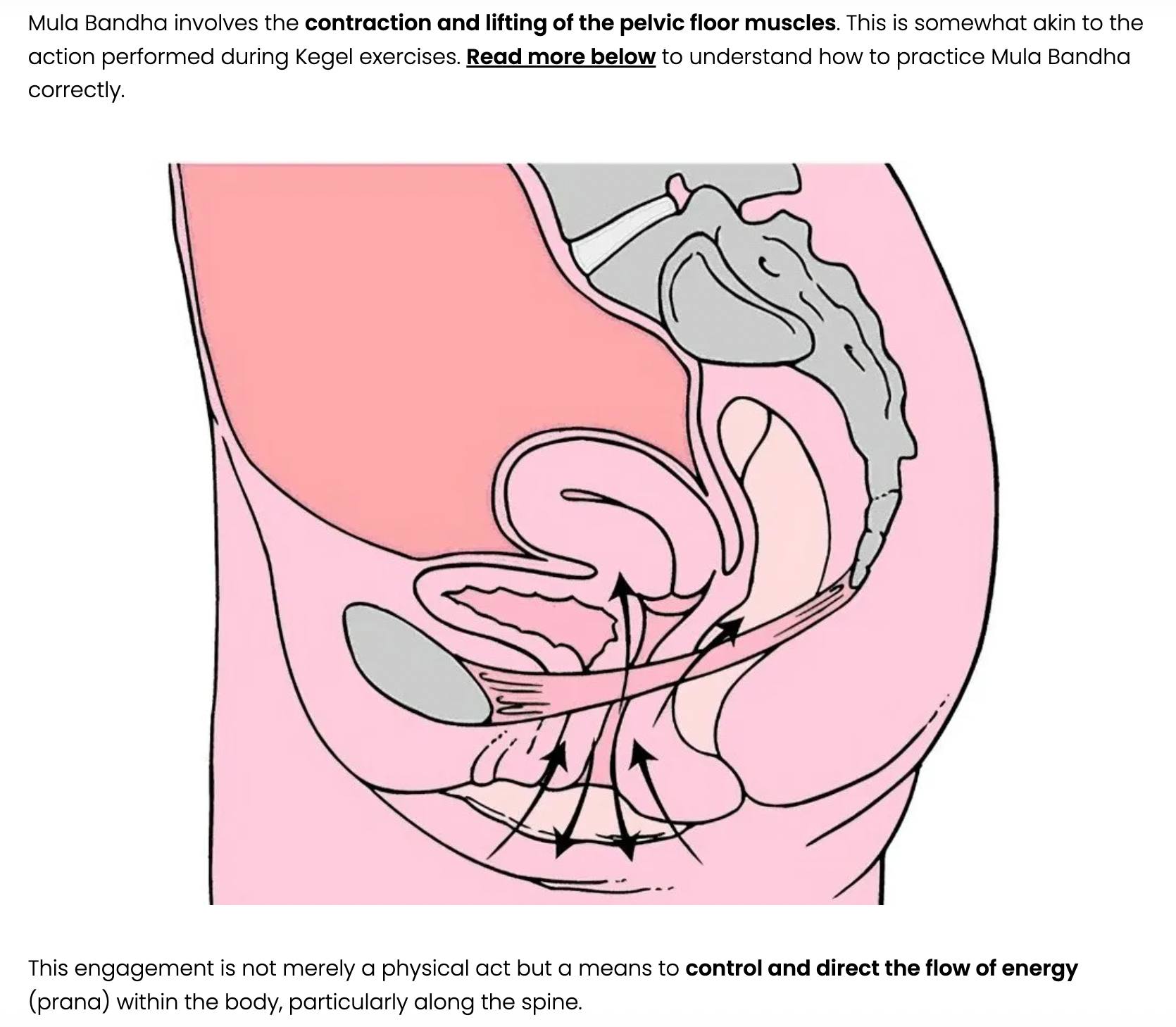

The pelvic floor essentially consists of layered muscle and connective tissue that sweeps from left to right and front to back of the pelvis, encircling, supporting, and largely controlling the actions of the three orifices (in women) that emerge at the bottom of the body, the urethra, the vagina, and the anus.

One set of pelvic floor muscles (PFM) attaches to the pubic bone in the front, and in the back, to the tail bone (coccyx). A second set of muscles stretches from sitting bone to sitting bone, left to right across the bottom of the pelvic bowl. All together these muscles are often likened to a hammock or sling.

Most of the time these muscles do their work without us noticing them. They are responsible for:

o Maintaining tone and being able to contract and release so that we have reliable control over processes of elimination and to create some protection about what enters these areas.

o Strong, flexible PFM can contribute to sexual function and pleasure.

o The pelvic diaphragm, another name for this muscle group, is considered one of the breathing diaphragms. It needs to be both toned and flexible for breathing to be full, relaxed, and deep.

o The PFM are also considered part of the “core” of the body. As such, they are implicated in postural integrity, stability and balance, and also essential to

o Creating a stable, strong floor to hold up all the internal organs above them. They literally keep our insides from falling out through our legs.

Except when they don’t…

Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP)

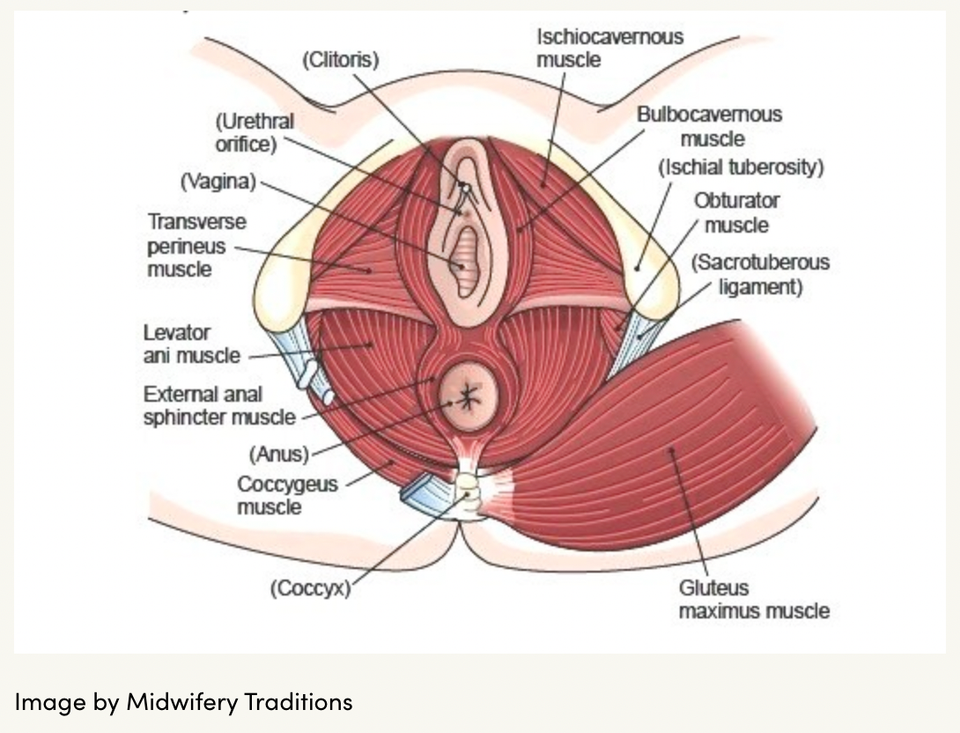

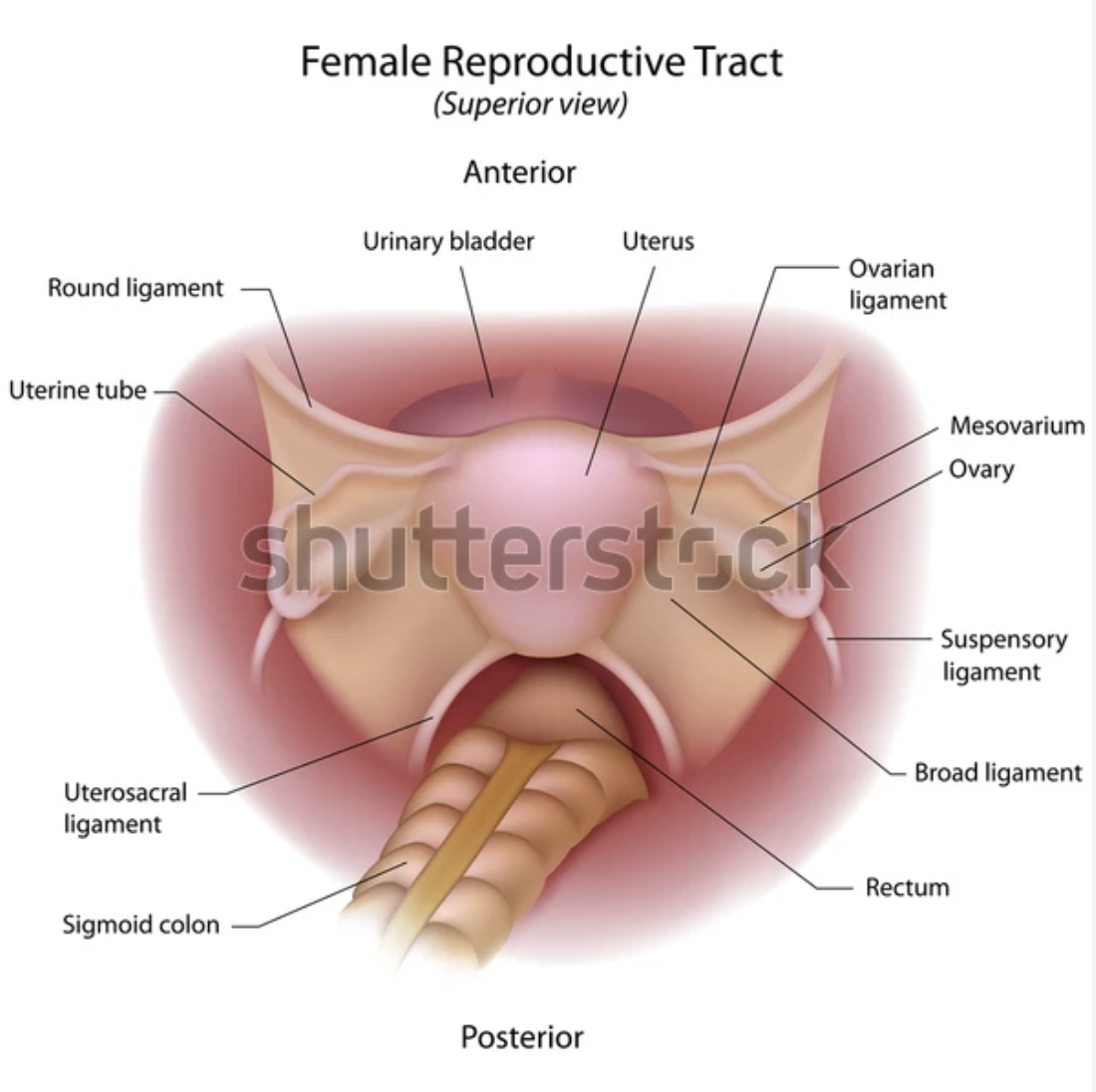

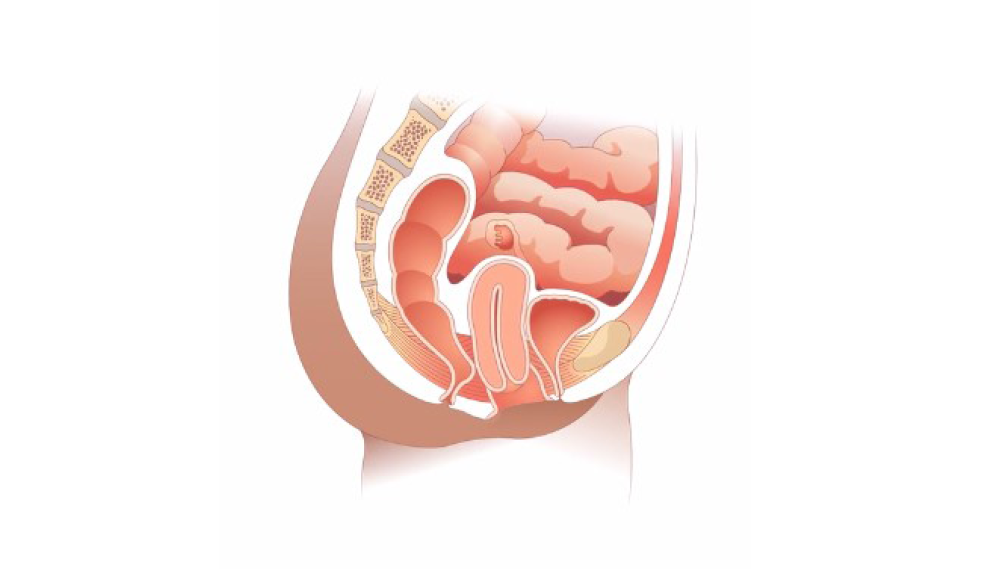

POP is a condition in which one or more of the structures of the pelvic region either impinges upon another organ (cystocele, rectocele, enterocele) or falls out of place (prolapse).

This is an excellent video from “Pelvic Empowerment” describing and illustrating what prolapse and cystocele and rectocele are:

(Time stamps in the video notes)

Essentially, prolapse refers to the descent of an organ through its respective tube: the bladder falls into the urethra, the uterus into the vagina, and the rectum into the anus.

“-cele” is a medical suffix that means “bulging” or “pouching.” In these cases, an organ or structure impinges on another, for example, the bladder might push into the vaginal wall resulting in pain with sexual intercourse or difficulty emptying the bladder fully.

POP-Q

The POP-Q is the pelvic organ prolapse quantification system and is used to “grade” the severity of a prolapse.

Degrees of uterine prolapse

Uterine prolapse is described in stages, indicating how far the uterus has descended into the vagina. The four categories of uterine prolapse are:

- Stage I – the uterus is in the upper half of the vagina

- Stage II – the uterus has descended nearly to the opening of the vagina

- Stage III – the uterus protrudes out of the vagina

- Stage IV – the uterus is completely out of the vagina.

(From the Victoria State Government Department of Health in Australia: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/prolapsed-uterus)

Although this example refers to uterine prolapse, it is also possible to have bladder, small bowel, vaginal vault (upper part of the vagina), or rectal prolapse. It is very common for people to have prolapse in more than one “compartment.” In other words, if a person has a uterine prolapse (apical compartment), they are also likely to have prolapse in the bladder area forward of the vagina (anterior compartment), or in the rectal area behind the vagina (posterior compartment).

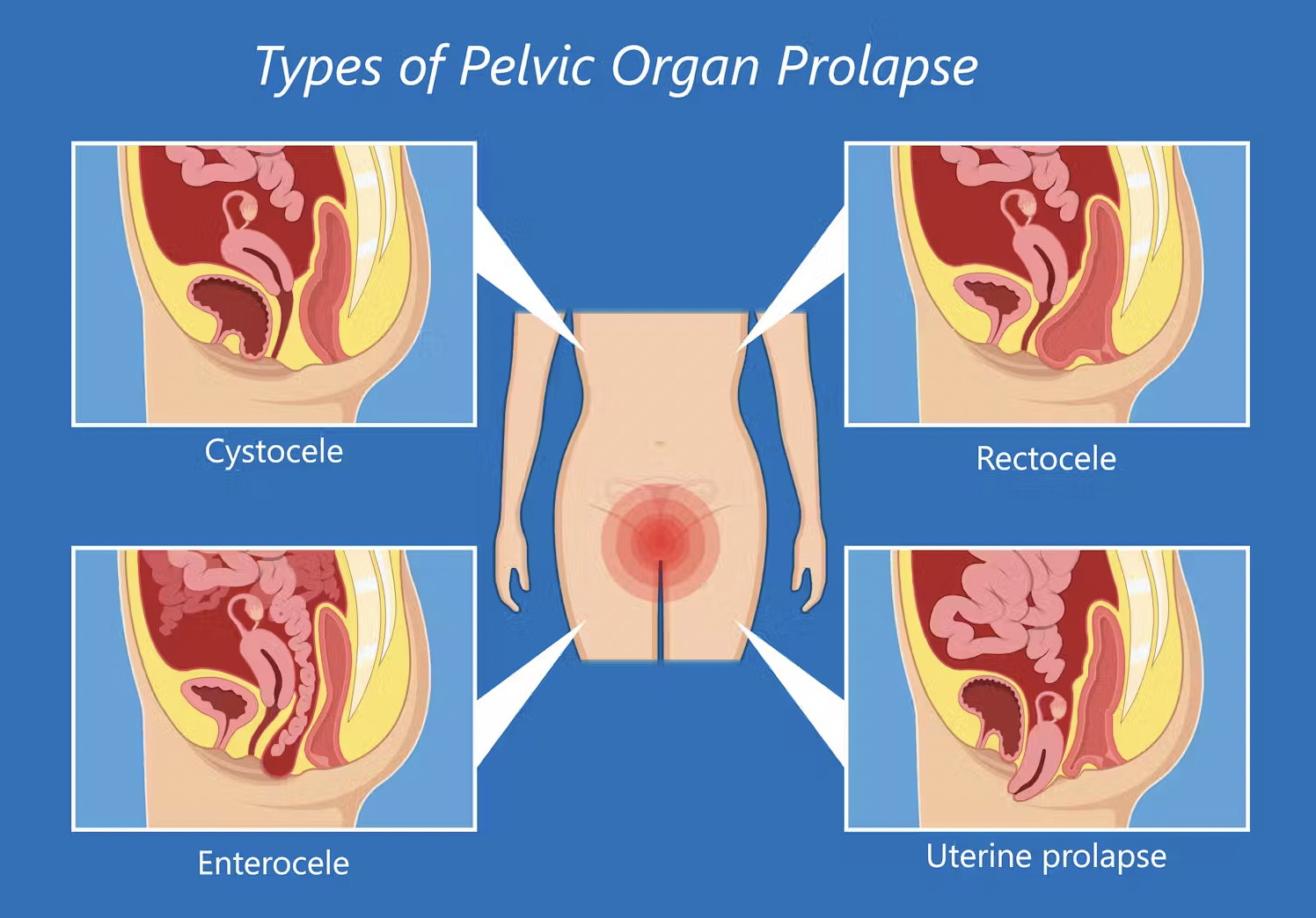

This makes sense because the most common and important factor contributing to the development of POP is a combination of weakened pelvic floor muscles and overstretched and weakened ligaments.

This is a great image from the “Pelvic Empowerment” video above that simply illustrates what the pelvic floor and ligaments offer the internal organs, which are pictured here as the boat:

How do the pelvic floor muscles and supporting ligaments of the pelvic organs become compromised?

There are multiple risk factors, and they tend to be common and wide ranging, which is part of why POP is so common.

Giving birth vaginally can be a risk factor. This is especially true if a woman has

o Given birth multiple times

o Given birth to multiples, i.e., twins, triplets

o Has had large babies

o Had a traumatizing birth experience, for example, forceps and/or vacuum extraction were used or she suffered large tears in the perineum that did not heal well.

Pelvic floor injury. This may include accidents that have injured the pelvic floor, surgeries or medical treatments, sexual abuse, or childbirth-related injuries.

Hysterectomy can increase the risk of prolapse in other organs because removing an organ changes the support structures inside. Suddenly an entire organ, perhaps with some of its supporting structures (ligaments), is gone. If the other organs can’t find alternate sources of support, they may start to collapse.

Obesity and overweight can create wear and tear on the pelvic floor as the increase in downward pressure places significant strain on the PFMf and requires them to do more work.

Anything that increases pressure or strain in the pelvic region. This includes:

Chronic constipation. Pressure builds up in the area so that tissues may become inflamed or overstretched. Additionally, people usually strain and bear down on muscles forcefully to try to eliminate backed up, hardened stool. This can be hard on the pelvic floor muscles (PFM).

Coughing, heavy lifting, and high-impact exercise also put strain on the area.

Research is demonstrating that genetics may play a key role in the development of POP. Lince et al. (2012) did a systematic review looking at the research that had been done on hereditary factors in POP. They noted some interesting results:

o One study “found a high rate of concordance between the POP stage of a parous [having given birth] woman and her nulliparous sister, thereby suggesting a familial predisposition toward the development of this disorder.”

o Another study found that POP was transmitted through both male and female relatives

o Ultimately, the writers concluded that women with at least one female family member with POP have a significantly higher risk of developing POP.

Another study by Li et al. (2024) looked in detail at how genetic pathways might account for the research indicating that “sisters of patients with severe POP are five times more likely to develop the condition compared to women without a familial history.”

o It’s possible that genes play a role in how easily connective and muscle tissue sustains injury and/or how well they heal.

o The researchers also found that genetic influence on cellular changes and metabolism could compromise how well PFM function. Unchecked oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, protein homeostasis imbalance, and inflammation could create pathologies in the tissues that contribute to weakness, vulnerabilities to tearing, and impaired healing.

o Interestingly, the authors did consider the questions of environment and epigenetics. In other words, do one’s genes create the conditions for pelvic organ prolapse to happen or does pelvic organ prolapse “turn on” certain genes that create more overstretching, weakness, and inflammation in the tissues? More investigation is needed to understand the complexity of genetics.

Li et al. (2024) also noted that the role of estrogen and progesterone in POP is unclear. Though both hormones contribute to the integrity of connective and muscle tissue, neither is therapeutic for POP and there is no data that either increases the efficacy of POP surgery.

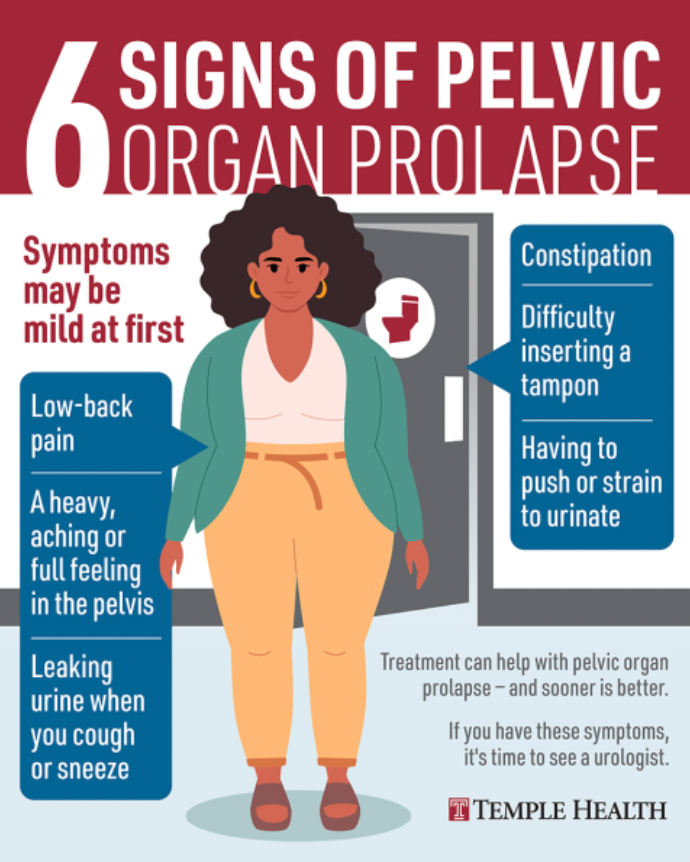

Symptoms of POP

o A feeling of fullness or pressure in the vagina or pelvis

o A sense of something “falling out” of the vagina

o Pressure or pain during intercourse

o Pain with sex, orgasm, in the hips or back, or in the pelvis generally

o Changes in how one pees or poops

o “Splinting” refers to the need to put one’s finger into the vagina in order to fully empty the bladder or rectum

o Stress incontinence

o Constipation or losing control of one’s bowels

Diagnosis

Typically, POP is diagnosed by a pelvic exam. The prolapse may be able to be seen and/or palpated. Muscle testing can also be done to see how well the muscles are contracting or, conversely, how tight they may already be. Ultrasound or MRI can also be used.

Treatments

Pessaries

“Pessaries are devices, often made of medical-grade silicone, that are positioned in the vagina to restore normal pelvic anatomy. They are an option for all stages of prolapse and are useful to prevent the progression of prolapse and can delay the need for surgery. 85% of patients are successfully fit for a pessary” (Aboseif & Liu, 2022).

Pessaries can be extremely helpful for many women, especially if the prolapse is not advanced, but they do need to be fitted for each individual by a doctor.

Here is a link to a PDF developed by a Pelvic Obstetric & Gynaecological Physiotherapy group in the UK that describes various types of pessaries and graphical illustrates their placement:

https://thepogp.co.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/pessary_types_guide.pdf

Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy

In more enlightened nations than the U.S., pelvic floor PT is typically considered an essential part of postpartum care, offered and paid for as a matter of course by national healthcare systems. It is supremely unrealistic to imagine that a woman’s body is going to magically regain its muscle tone and structural integrity without any guided or conscious effort, especially if she has given birth multiple times or endured any birth trauma. When most people think about “getting into shape” after giving birth the focus tends to be on fitting back into pre-pregnancy jeans, not on the pelvic floor and tissues of the core.

Childbearing could conceivably be thought of as an extreme sport. Muscles in the pelvic region stretch and contract dramatically in unique ways during both pregnancy and childbirth. Relaxin, a hormone produced by the ovaries and placenta during pregnancy, further loosens muscles, ligaments, and joints so that bones can shift easily to make space for a growing fetus as well as to permit passage of the baby through the birth canal. Although relaxin diminishes and production stops after pregnancy, some ligaments may remain in a lax state and joints may not be holding bones in quite the same relationship to each other as before birth.

Although I am emphasizing the changes of pregnancy, pelvic floor health is a concern for all women. Trauma/injury to the area, surgery and medical treatments, or simply the changes inherent in menopause and aging all have an impact on the pelvic floor area. Most women will benefit at some point in their life from learning more about how to care for these tissues.

If one does not have pain or prolapse symptoms, it may be possible to read a book or find a video about pelvic floor exercises to strengthen and tone the PFM. The pelvic floor therapists I have heard/read discourage this approach.

The reason for this is because it can be very difficult for an individual to know if their PFM are too lax/weak or too tight. If the muscles are too tight, doing more Kegels—an instruction women are often given either in magazine articles or by doctors—will make things worse, exacerbating the spasm in the pelvic floor and creating more dysfunction.

Whether lax or tight, the PFM will be weak. And, as you can imagine from looking at all the directions in which the pelvic muscles flow, they each have different ways to contract and release that need to be addressed. There are more varied and important ways to exercise and release these muscles than Kegels alone!

Make sure to seek out a certified pelvic floor physical therapist/specialist for help with POP.

A word on exercise and the “core”

What is the “core”?

I think most people tend to think of the core muscles as the abdominal muscles, especially the superficial ab muscles like the “six-pack” or “obliques.” Some will include the lower back muscles.

But when we think about the “core” of the body it is more accurate to consider the muscles that

o Create and sustain our postural integrity

o Keep our viscera—our organs and guts—protected and contained in the pelvic bowl

o Support balanced, stable, healthy, and powerful movement from the center of our bodies out through the limbs

The deep, core muscles include

o The psoas and iliacus, which support the lumbar spine and connect the spine through the hips to the legs

o Transversus abdominus (our internal corset)

o Quadratus lumborum, which connects the rib cage to the pelvis on each side

o Pelvic floor muscles

Exercise such as abdominal crunches or lifting weights can trigger or exacerbate pelvic floor issues when we hold our breath and bear down while exerting or lifting. It can become a habit for people to hold their breaths when under stress, whether that stress is voluntary or involuntary. When this happens, a person tends to breathe in so that the belly extends and the lungs are full and then holds the breath so that the core muscles stay stretched.

When someone tries to lift or exert effort in this state, the stretched muscles of the abdominal region and pelvic floor are unable to contract to support the effort and protect the internal organs. Additionally, the intra-abdominal pressure is increased and that extends the tissues further, compromising their structural integrity and the well-being of the organs.

Our body is designed so that our core muscles naturally contract to help us exhale. If we inhale a full breath and then exhale, allowing our core muscles to move freely as we exert ourselves and/or lift, our abdominal and pelvic floor muscles will naturally contract, lifting in and up to

o support our spine and upper body

o release air and pressure in the abdominal region

o focus musculoskeletal energy and power up and out in the direction we’re working

Yoga and Pilates are excellent forms of exercise for learning how to connect with, strengthen, and tone the pelvic floor.

Surgery

There are basically two categories of surgery used to address/repair POP:

o Obliterative, also called colpocleisis. Appropriately named, this is when the vagina is essentially closed, stitched up so that it acts as a support for a prolapsed uterus.

o Reconstructive. In this type of surgery, mesh is used to construct exogenous support for various structures or stitches are used to reconnect and tighten up connections between organ and endogenous supports like ligaments.

What I have gleaned from my reading is that there are many ways in which a surgeon might approach repairing POP. Generally, repairing POP involves shoring up support from underneath (the pelvic floor) or tightening up the guy wires from above (the ligaments). Sometimes surgeries will incorporate some combination of both and/or hysterectomy and this makes sense when one considers how often multiple compartments are involved in prolapse.

Here are links to a couple of medical sites that describe surgeries for POP:

A few important things to keep in mind:

The doctor you want to see for POP questions and treatment is a urogynecologist! The pelvic floor can be a tricky place to navigate, so if you are considering surgery, you want to find a doctor who does a high-volume of these types of surgery and has lots of experience.

“Adequate support of the vaginal apex has been recognized as an essential component of an adequate surgical repair for advanced prolapse” (Aboseif & Liu, 2022). What this means is that even if a surgery is focused on creating support from below in order to lift a prolapsed organ, the surgery is more likely to be successful if the vaginal apex, i.e., the top of the vagina is supported, usually by being stitched up and back to ligaments in the wall of the pelvis or lower back.

Grafts/mesh:

o Native tissue, i.e., one’s own tissue from the pelvic region, can be used to repair tears or shore up weaknesses in the pelvic region in an attempt to relieve prolapse. The downside of this is that often the native tissues are fragile and weakened, which is why the the prolapse is occurring in the first place.

o Xenografts are tissue grafts from a non-human species, for example, pig.

o Allografts are from a human donor that is not genetically identical, for example, a cadaver.

o Mesh is a common, but controversial option. Apart from the grafts mentioned above, meshes are made from synthetic materials. Multiple studies have been done, none of which can conclusively say that one kind of mesh is better than another or that mesh should never be used. However, it is advisable for anyone considering the use of mesh in any kind of surgery to do research and ask lots of questions. Things to keep in mind:

o The skill and experience of the surgeon matters. From what I’ve read, a surgeon’s familiarity with the pelvic landscape and skill in placing mesh can make a big difference. “Studies have shown that inexperienced and low-volume surgeons have higher rates of complications that do experienced, high-volume surgeons” (Cardenas-Trowers et al. 2021).

o Transvaginal approaches, while less invasive and involving less recovery time than abdominal approaches, tend to lead to more complications and dissatisfaction post-surgery.

o Apical support is an essential component of adequate POP repair: “It has been established that addressing the vaginal apex at the time of reconstructive POP surgery contributes to a more durable POP repair” (Cardenas-Trowers et al., 2021).

o Quality of the musculature that will hold the mesh. “…the anchoring of mesh to musculature that is already hypertonic [tight] and spastic may perpetuate and exacerbate preoperative dyspareunia” (Gomelsky et al., 2011).

o Properties of the mesh itself. “Several studies suggest that polypropylene mesh may retract or contract after implantation” (Gomelsky et al., 2011).

o Comorbidities: Contraindications to mesh use reported by Gomelsky et al. (2011) include pelvic irradiation, severe urogenital atrophy, immunosuppression, active infection, diabetes, obesity, and heavy smoking.

o Women who have had mesh used in various pelvic repairs have been preyed upon by personal injury lawyers whether or not they have experienced complications.

Here is a link to some complications that could arise with mesh:

Not all bad

Although the information on the above site is scary and the use of mesh controversial, Dr. Gunter makes a good point when she says, “Lumping all mesh together is like lumping every motor vehicle together, from cars that have passed safety inspections and get high ratings from Consumer Reports to dune buggies with no air bags or seat belts” (Gunter, 2021). The right type of mesh in the hands of an experienced surgeon could greatly improve quality of life for some women.

Knowledge, support from others who have experienced POP and can guide you toward responsible professionals, and self-advocacy are key to maximizing one’s odds of satisfactorily addressing POP.

Recurrence

A meta-analysis of studies conducted by Shi & Guo (2023) found that of 6597 patients in Europe, America, Australia, and Asia, “2419 cases had recurrence after operation for POP, with a recurrence rate of 37.7%” (p.5). The risk of recurrence seems to be dependent on several factors:

o Operation type

o Severity/Grade of the original prolapse

o Number of previous operations (If someone has had a pelvic floor surgery previously, they are more likely to need a second or third.)

o History of hysterectomy

o Obesity/overweight

o Smoking

o Constipation

o Diabetes

o COPD

Prevention of recurrence

Lifestyle changes: weight loss, smoking cessation, dietary changes

Pelvic floor physical therapy ought to be considered an essential adjunct to any kind of POP surgery. Although a surgeon may not believe it to be essential, it seems obvious that anything one can do to strengthen and support the pelvic organs after needed prolapse repairs is likely to help maintain the repairs and prevent recurrence.

Race & Ethnicity

Interestingly, both studies looking at hereditary influences on POP found that race and ethnicity affected both the prevalence (how common it is) of POP and, possibly, the etiology (origin/cause) of POP.

Unsurprisingly, another group found that there are differences in how women of different races are treated for POP. In their 2021 study, Cardenas-Trowers et al. found that:

o “…despite Black women being the youngest racial group…[they] had the longest operating room time and postoperative length of stay of all racial groups” despite having similar surgeries to White and Hispanic women.

o Black women had the highest rates of baseline comorbidities.

o “Hispanic and other minority women had lower odds of undergoing [apical suspension] compared with White women.”

o “Obliterative [as opposed to reconstructive] procedures were more likely to be performed in Black, in Hispanic, and especially in other minority women.”

o “Studies have found that women are generally unknowledgeable about POP, but minority women are significantly less knowledgeable than White women about curative treatment options for POP like surgery.”

Although the scope of the authors’ research did not extend to exploring specific causes of care inequities in POP, they do suggest that social determinants of health play a substantial role.

POP does not only happen in aging women!

Clearly experience and research shows that pregnancy and childbearing is a huge risk factor for POP. Aware doctors often encourage women in their “fourth trimester,” the postpartum period, to get checked for or keep an eye out for symptoms of organ prolapse. Pelvic PT started during this period can restore core integrity, potentially protect the body in the event of future pregnancies, and prevent deterioration associated with aging. Carroll et al. (2022) did a qualitative study with fourteen women aged 32-41, half of whom had suffered traumatic births.

It broke my heart to read these women’s words. Many of them were frustrated what they saw as “the normalisation of pelvic health issues” in women and “that women’s bodily integrity is seen as being secondary to the wellbeing of their babies.” They also felt pressure to prove they were able to cope with being a new mom even as they struggled with pain, exhaustion, and fear about worsening their condition through exertion.

Critically, lack of knowledge on the part of both the women and their doctors, contributed to fear, anxiety, and deterioration of their situation. Most of them had been told by their doctors simply to avoid doing much and accept that the situation would get worse! Because women were afraid to engage in exercise, not only did their physical states decline, but depression, anxiety, tension, and loneliness increased.

However, POP progression is not a foregone conclusion:

According to the authors of the study, “The POP literature has noted a lack of data regarding POP progression and regression, as well as a widespread acceptance that POP is a progressive condition…However, research has demonstrated that POP regression occurs in 19-48% of women with stage 1 or 2 prolapse without intervention over three to eight years, while other research demonstrated 21% regression with the use of vaginal support pessaries” (Carroll et al., 2022, italics mine).

Conclusion

I know this has been a sobering post. However, what I would like anyone who is reading it to take away it is this:

Pelvic floor weakening and organ prolapse are not inevitable, nor are they incurable.

AND

It's important to be proactive in caring for one's pelvic floor and internal organs.

There is a lot that can be done–without surgery–to strengthen and relax core muscle groups so that collapse and downslide can be corrected to the point of complete remission or being asymptomatic. And multiple effective surgical interventions do exist that can greatly increase quality of life and well-being for women.

However, even if one is not experiencing any symptoms of POP or bladder problems, pelvic floor laxity and tension tends to increase with age, even if only because of the strain of gravity over the decades. It is in our own best interest to explore our pelvic health and fitness, especially if we have any of the known risk factors for POP, and proactively cultivate strength to prevent future problems. In the case of POP, an ounce of prevention really is worth a pound of cure.

Resources

I know there is already a lot of information in this post, but here are two more links to sites that might be helpful:

A 2025 post on the ACOG (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologist) site entitled “5 Things I Wish All Women Knew About Pelvic Organ Prolapse:”

A link to the American Urogynecologic Society’s site where you can find “fact sheets” about a variety of pelvic floor dysfunctions (PFDs):

References

Aboseif, C., & Liu, P. (2020). Pelvic organ prolapse. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563229/

Belayneh, T., Gebeyehu, A., Adefris, M., Rortveit, G., Gjerde, J. L., & Ayele, T. A. (2021). Pelvic organ prolapse surgery and health-related quality of life: a follow-up study. BMC Women's Health, 21, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01146-8

Cardenas-Trowers, O. O., Gaskins, J. T., & Francis, S. L. (2021). Association of patient race with type of pelvic organ prolapse surgery performed and adverse events. Urogynecology, 27(10), 595-601. DOI: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001000

Carroll, L., O’Sullivan, C., Doody, C., Perrotta, C., & Fullen, B. (2022). Pelvic organ prolapse: The lived experience. Plos one, 17(11), e0276788. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276788

Cleveland Clinic: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24046-pelvic-organ-prolapse

Dietz, H. P., Socha, M., Atan, I. K., & Subramaniam, N. (2020). Does estrogen deprivation affect pelvic floor muscle contractility?. International urogynecology journal, 31, 191-196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-03909-w

Gomelsky, A., Penson, D. F., & Dmochowski, R. R. (2011). Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery: the evidence for the repairs. BJU international, 107(11), 1704-1719. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10123.x

Gunter, Jen. (2021). The Menopause Manifesto. Citadel Press.

Li, Y., Li, Z., Li, Y., Gao, X., Wang, T., Huang, Y., & Wu, M. (2024). Genetics of female pelvic organ prolapse: up to date. Biomolecules, 14(9), 1097. doi: 10.3390/biom14091097

Lince, S. L., van Kempen, L. C., Vierhout, M. E., & Kluivers, K. B. (2012). A systematic review of clinical studies on hereditary factors in pelvic organ prolapse. International urogynecology journal, 23, 1327-1336. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1704-4

Moon, J. W., & Chae, H. D. (2016). Vaginal approaches using synthetic mesh to treat pelvic organ prolapse. Annals of Coloproctology, 32(1), 7. doi: 10.3393/ac.2016.32.1.7

Shi, W., & Guo, L. (2023). Risk factors for the recurrence of pelvic organ prolapse: a meta-analysis. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 43(1), 2160929. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2022.2160929

Image References

Title image: https://www.ladybirdpt.com/post/demystifying-the-pelvic-floor

Types of POP: https://theconversation.com/what-is-pelvic-organ-prolapse-and-how-is-it-treated-239199

Signs of POP: https://www.templehealth.org/about/blog/recognizing-pelvic-organ-prolapse

Mula bandha: https://oneyogathailand.com/the-essential-guide-to-mula-bandha-for-beginners/

Ounce of prevention: https://condenaststore.com/featured/ill-have-an-ounce-of-prevention-dana-fradon.html