Intersectionality

What is intersectionality?

Much of how we interpret any life event—including the menopause transition—has to do with

· our unique perspective on that event

AND

· how we contextualize it and ourselves in relationship with what is happening to us or what we are causing to happen

We each exist at the intersection of multiple identities, and this makes our individual experiences of life more or less complex depending on how many overlapping identities we have and how many characteristics we share with the dominant group.

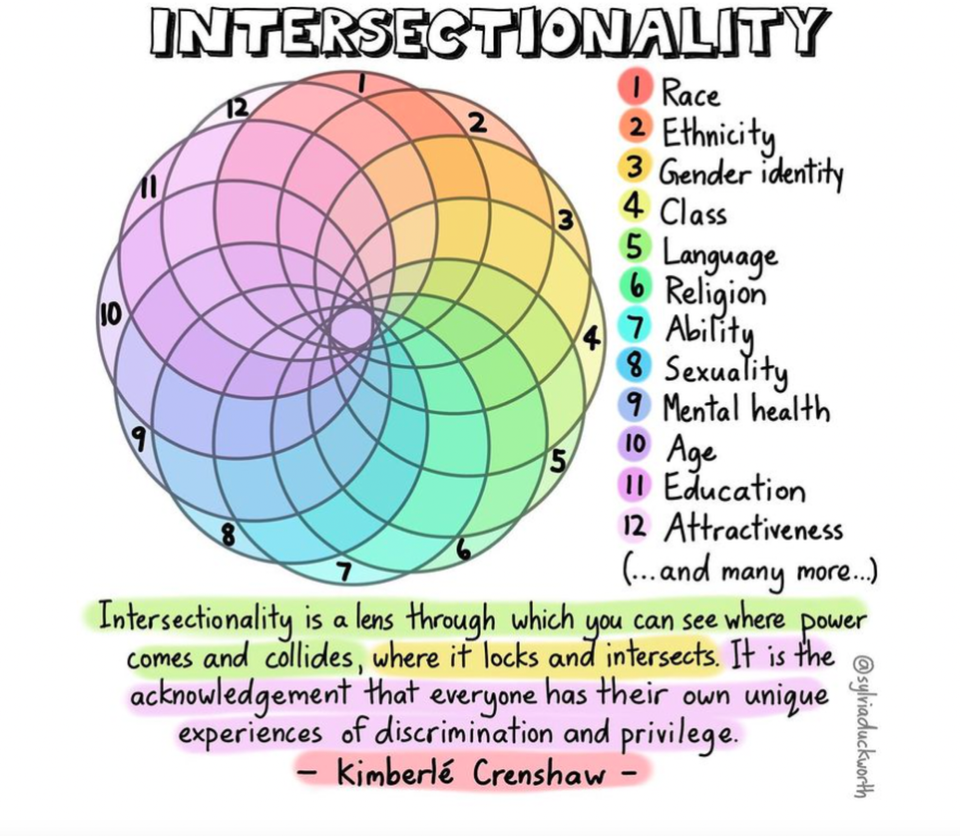

This is a very simple image denoting intersectionality, and most of us have a range of groups we belong to that contribute to the make-up of our individual identity. These groups can include race, ethnicity, and religion, but may also include things like zip code, volunteer at Planned Parenthood, or vegan activist. The physical and mental characteristics we have, as well as the relationships, activities, and groups that we invest in and identify strongly with all contribute to how we vote, behave, spend our money and time, and also how we are perceived and what others believe about us and how they treat us.

In American culture, from its inception to the present day, the power dominant group is the White, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied male who was born with access to wealth, higher education, and the echelons of power and who is sympathetic to Christian theocratic aims.

In her 1989 paper, Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, judicial scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to describe the unique status and forces of oppression experienced by Black women in the United States.

There are (at least) four critical points to understand about intersectionality:

Power & Disadvantage

First, where we sit within the overlapping of our identities shows us both what kinds of power and privilege we have as well as where we are disempowered and vulnerable culturally/socially/politically.

For example, three characteristics of my identity are White, college-educated and female. I am privileged and able to wield power because of my race and educational status and at the same time I am systemically oppressed and made uniquely vulnerable because of my gender. A further refinement of this intersection would be to acknowledge that I am cisgender and heterosexual, so theoretically and at times materially, I wield more power as a female than lesbian or queer women or those females who do not identify as women.

Invisibilization (Is that a word?)

Second—and this is a point that Crenshaw focused on in her paper—the intersection at which a person stands makes that person more or less visible in the eyes of the law, society, and culture. Crenshaw used three Title VII (antidiscrimination) legal cases to describe intersectionality and how it works practically.

In one case, a black woman filed a sex discrimination suit “on behalf of all women” at a helicopter company. Ultimately, a circuit court found that since she had claimed to be discriminated against “only as a Black female…[T]his raised serious doubts as to Moore’s ability to adequately represent white female employees” (p.144). Basically, the court thought a Black woman incapable of representing the category “female.”

In another case Black women sought to bring a racial discrimination suit against a company. However, “The court refused…to allow the plaintiffs to represent Black males…” (p.147). In this case the women were permitted to represent the class “Black women,” but were not allowed to represent men of the same race.

Finally, and most damningly, a suit was brought against General Motors by a Black woman alleging sex discrimination because of the system of promotion that was used. Ultimately, the court found that because the woman was a Black woman, she was not due protection from either discrimination based on gender, nor on discrimination based on race. She was something “other” that was “neither” and ended up being essentially “nothing” in the eyes of the law.

What the court said was “The legislative history surrounding Title VII does not indicate that the goal of the statute was to create a new classification of ‘black women’ who would have greater standing than, for example, a black male. The prospect of the creation of new classes of protected minorities, governed only by the mathematical principles of permutation and combination, clearly raises the prospect of opening the hackneyed Pandora’s box” (p.142, italics mine).

In other words, this court could not risk seeing or recognizing a legal class of "Black women" because it was concerned it would then have to legally recognize the experiences of groups and individuals with multiple intersecting identities, hearing and ruling on cases having to do with the specific and unique ways these groups and individuals are discriminated against.

And so the term invisibilize comes into vogue to describe the ways in which entire groups of people become legally invisible and, in the process of erasure, become increasingly marginalized and vulnerable to abuse.

Interestingly, there is a group that profits by a type of invisibility, with the resulting profit also often rendered invisible. This would be those in the dominant group. As Crenshaw points out, “because the privileging of whiteness or maleness is implicit, it is generally not perceived at all” (151). We are so accustomed to viewing whiteness, maleness, genderedness as the “norms,” that we tend not to see them or the benefits that accrue to them; we see only what contrasts with them.

Seeing and being seen

The third thing to keep in mind about intersectionality is that identification goes both ways: We are always seeing others and being seen by others. Others are making assumptions and asking themselves questions about us, just as we are with them.

Greater than the sum

A fourth thing to appreciate about intersectionality is that any point on the diagram is greater than the sum of its parts. Crenshaw writes, “Black women’s experiences are much broader than the general categories that discrimination discourse provides…the continued insistence that Black women’s demands and needs be filtered through categorical analyses that completely obscure their experiences guarantees that their needs will seldom be addressed” (p.149-150).

The life of a poor White male miner will never be described by the simple arithmetic of adding up poor + White + male + miner. The overlapping of all those characteristics, plus religion, geography, education, birth order, etc. all comprise a unique life experience within this particular culture that cannot be easily summed up by piling stereotypes on top of each other.

This is what the court was afraid of

If every individual has their own unique experience of discrimination and/or if individuals are willing to band together into groups that acknowledge a shared discrimination, where will it end?

After all, many characteristics such as race, gender, sexual orientation, physical ability may appear to be definitive, distinctive, unalterable, and easily categorized. However, as we have witnessed in just the last few decades, these categories are blurring more and more.

· According to Wikipedia, as of 2019 19% of new marriages in the U.S. are interracial, up from 3% in 1967. Any offspring from these relationships are going to be multiracial, defying easy categorization.

· The vocal emergence of trans and genderfluid groups and people into the mainstream culture have made it impossible to adhere to a simple binary understanding of gender identity or sexual expression.

· Attributes such as physical ability, intelligence, and health are no longer considered intractable harbingers of destiny. Those who understand the impact of systems on individual lives also understand that how a blind person or a person who doesn’t do well on standardized tests is treated and educated has an impact on that person’s access to economic power, meaningful work, and sense of belonging in the community and culture.

· Further, how any person’s health is valued and supported, or not, will create variation across any category labeled “healthy” or “diseased.”

The vast majority of us do differ in multiple ways from the small subset of the dominant group that seeks to reify and wield its abnormal levels of power and access to resources. The last several decades have been a time of intensifying vocalization and self-description by people who are demanding

· that their differences from the dominant group be seen and acknowledged

AND

· the oppressions they have suffered and do endure because of those differences stopped

Although this process has been characterized and presented to us as an ivory tower academic’s “woke” fever dream, the truth is that this recognition and acknowledgment of what has been perpetrated by a small powerful clique on all those who are not part of this select "in-group," is happening at a grassroots level as people live their lives.

It feels like a hot mess at times. Sort of like menopause.

What else does this have to do with menopause?

As I said at the beginning of this post, how we understand ourselves and how we are perceived within our cultural, social, political, and familial contexts, affects how we approach and integrate our life experiences. In the next post I will be considering how race and gender identity may impact the experience of menopause.

An understanding of intersectionality grounds this information in an appreciation of how complex individual experience may be and helps us avoid a reductionistic view of ourselves and others. Having a more nuanced appreciation for how individuals and groups can be both exaggerated and eclipsed by stereotypes and systems may give us more compassion as we look at statistics, as well as a greater ability to understand the implications and shortcomings of research findings for all of us.

References

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139.

Interracial marriage in the United States. (2025, April 2). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interracial_marriage_in_the_United_States#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20interracial%20marriages,1967%20to%2019%25%20in%202019

Title Image Reference: