(GSM) Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause

What’s in a name?

GSM is a collection of symptoms affecting the vagina, vulva, clitoris, urinary tract, and bladder. Although it is typically considered a syndrome concomitant with menopause, some of these symptoms can also affect women who breastfeed for more than six months, those who take oral contraceptives, and even people who take antidepressants (Hudson, 2025). This is because the decline in estrogen levels seems to be primarily responsible for the symptoms of GSM.

Originally, the symptoms of GSM were known as “vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)” or “atrophic vaginitis.” In 2014 the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) recommended using “genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM)” instead. Doust et al. (2023) note three reasons for this change:

· The previous descriptions contained negative connotations with the word “atrophy,” which comes from Latin and Greek roots meaning “wasting away” and “under- or malnourished.”

· The older terminology “did not encompass all the genital and urinary symptoms associated with endocrine changes in the perimenopause and postmenopause.”

And my favorite,

· “’the word vagina is not a generally accepted term for public discourse’”

It seems if we’re going to do research and have an open, public discussion about women’s bodies, we’re going to have to neuter them first.

Prevalence & Reporting of GSM

The percentage of women affected by GSM seems to range from 50-60% overall. However, there are a few reasons to be skeptical about these numbers:

1. Vaginal dryness, the most prevalent and widespread symptom of GSM, can affect up to 93% of women and “the most predominant complaints of sexually active women are reduced lubrication and dyspareunia (pain with sex, particularly penetration), the prevalence of which has been reported to be 90% and 80% respectively” (Angelou et al., 2020).

2. Vulvovaginal symptoms tend to go underreported and undertreated for a variety of reasons (Nappi & Kokot-Kierepa, 2010):

a. Discomfort and embarrassment discussing vaginal symptoms, even with doctors

b. Not knowing that these symptoms are not simply a sign of “normal” aging and that there are simple, safe, and effective treatments available

c. General lack of knowledge and accessible, evidence-based information about vaginal and pelvic health and issues related to them

d. Acculturation, or as Dr. Jen Gunter puts it, “Women are constantly expected to tolerate the consequences of their biology” (Gunter, p.179).

e. The reluctance of healthcare professionals to address vulvovaginal symptoms (Angelou et al., 2020), as well as the lack of education and awareness among healthcare professionals about these genitourinary issues in women (Hudson, 2025), also contribute to the silence and ongoing absence of information about GSM.

3. There is some evidence that, unlike other symptoms common during perimenopause, GSM symptoms can emerge and intensify in the postmenopausal years, becoming worse and more difficult to reverse if left untreated (Angelou et al., 2020; Hudson, 2025). However, Doust et al. (2023) have stated that “this is not supported by prospective evidence. Whether or not GSM symptoms are progressive without treatment is unknown” (p.7).

Symptoms of GSM

In addition to vaginal dryness, symptoms of GSM include the following:

· Itching/burning

· Pain with penetrative sex (dyspareunia)

· Generalized vaginal, vulval, and/or pelvic pain, especially tenderness at the introitus (entrance to the vagina)

· The labia thin and regress

· Graying and thinning of pubic hair

· Degeneration (atrophy) of smooth muscles in vagina and pelvic floor (which contains both smooth and skeletal muscle)

· Decreased lubrication

· Feeling of tightness in the tissue

· Leukorrhea (thin, white or milky vaginal discharge—not abnormal unless it smells bad, is yellowish or green, or is accompanied by itching/burning)

· Decreased libido

· Decreased strength of and/or longer time in reaching orgasm

· Dysorgasmia (pain with orgasm)

· The clitoris becomes smaller and the amount of erectile tissue decreases, though whether this is related to estrogen decline or simply aging is undetermined

· Vaginal vault prolapse (when the upper part of the vagina descends into the lower part due to pelvic floor muscles weakening)

As estrogen becomes scarcer, collagen and glycogen production are reduced and blood flow in the pelvic and genital region diminishes. This causes the vaginal epithelium (the specialized tissue that lines the vagina and provides a barrier to infection and injury) to thin. It also makes the tissues of the vulva, vagina, urinary tract, and bladder less elastic, more fragile, and therefore more prone to small lacerations or tears that make the area vulnerable to viruses and harmful bacteria.

In addition, changes in the vaginal microbiome tend to involve dramatic reductions in protective, immune-enhancing Lactobacillus microbes, which gives opportunistic, more infectious bacteria a chance to thrive.

This profound anatomical and biochemical remodeling of a woman’s genital region leaves her at increased risk for:

o Urinary urgency, increased frequency, or dysuria (pain with urination)

o Stress incontinence (peeing when coughing, laughing, or with abdominal contraction)

o Urinary tract infections (UTIs) and/or bladder infections

o Sexually transmitted diseases

o Other infections such as bacterial vaginosis

o Autoimmune skin conditions such as lichen sclerosus and lichen planus

(Angelou et al., 2020; Athanasiou et al., 2016; Doust et al., 2023; Gunter, 2021; Mitchell et al. 2023; Muir, 2023)

Diagnosing GSM

It’s important to note that there are objective, anatomical changes that occur in GSM, for example, visible and measurable alterations in the muscles and tissues or the microbiome and pH of the vagina. But there are also subjective, experiential changes—pain with sex, irritation and burning, decreased libido, and urinary/bladder discomfort—and these tend to be the reasons women suffer and why they seek treatment, if they do.

Researchers and healthcare practitioners can look at the size and condition of the vulva, labia, and vagina to see signs of GSM, or they can measure things like severity of pain at the vaginal entrance using cotton swabs (Mitchell et al., 2023), pH levels in the vagina, or use the VMI (the Vaginal Maturation Index) to determine the “maturity” of cells inside the vagina, which gives a glimpse into estrogen levels (Doust et al., 2023).

But the vast majority of healthcare professionals don’t know enough about menopause and GSM to know what to look for or how to diagnose based on anatomical and physiological changes in the genitals. And, as Doust et al. (2023) point out, “Using…’objective’ measures as part of the diagnostic criteria can cause harm, by excluding those who may benefit and including those who will not” (p.9).

Most of the time, doctors cannot even imagine the root causes of the symptoms women are subjectively suffering. In Hudson’s 2025 article in The Guardian, she describes the experiences of women who found wiping after peeing painful, who were too sore to wear underwear, sit, work out, or walk, and even a woman who had to quit multiple jobs, sell her home, and move away from her social network because she’d been told by her GP to “prepare herself for a life of chronic pain.” This was even after she had “paid to see a private vulval pain specialist!” WTF?! (Within two days of starting on vaginal estrogen--something she had to research and ask her GP for--the burning that "felt like a red hot poker" stopped and she was on the road toward recovery, though still struggling with UTIs.)

Additionally, it is possible, even likely in some cases, that not all symptoms attributed to GSM actually have to do with the hormonal fluctuations and decline of menopause. Many of the urinary symptoms, particularly urgency, frequency, or incontinence, may be due to a weakened pelvic floor, which can be caused by pregnancy and childbearing, obesity, or simply a chronic lack of muscle tone that has gotten worse with aging.

Angelou et al. (2020) reported “urinary symptoms are considered less frequent” than other symptoms of GSM and mention risk factors apart from menopause and estrogen deprivation, including:

· Absence of vaginal childbirth

· Alcohol abuse

· Decreased frequency of sex and sexual abstinence

· Cancer treatments such as pelvic irradiation, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy

· Comorbidities involving the urogynecological systems

· Low education levels

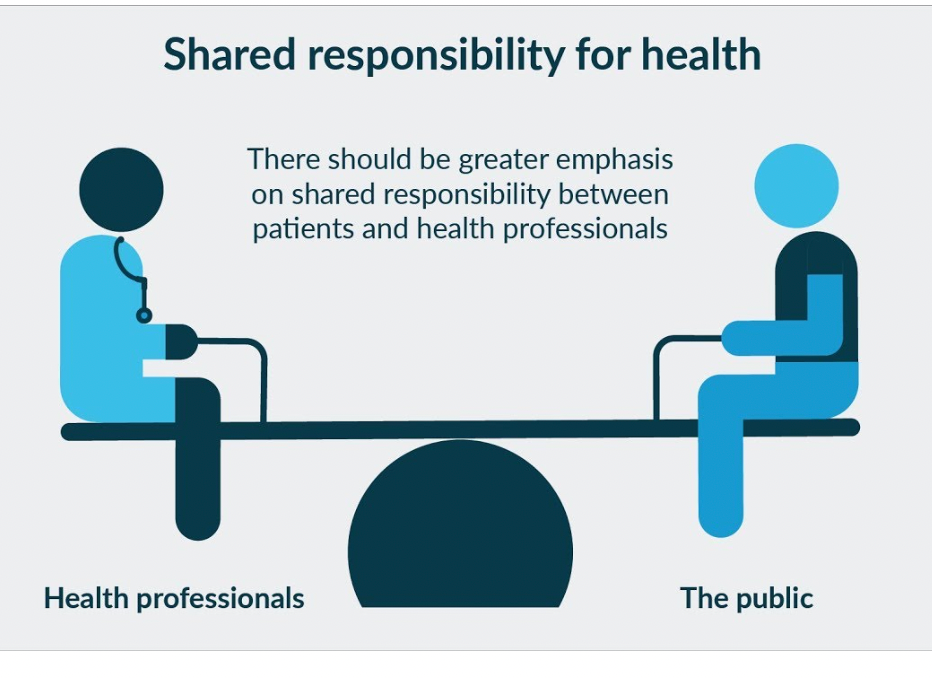

This all points to the importance of taking a patient-centered approach to diagnosing and treating symptoms of GSM.

Tools for understanding patient experience of GSM

In the process of researching GSM I ran across some interesting tests (like the VMI) and questionnaires I had never heard of. A few instruments have been developed specifically to gauge severity of GSM symptoms.

The “Vulvovaginal Symptoms Questionnaire” asks about physical, emotional, and sexual symptoms of GSM and their social and life impacts.

Information about the questionnaire: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Vulvovaginal_Symptoms_Questionnaire_(VSQ)

The questionnaire itself: https://cdn-links.lww.com/permalink/meno/a/meno_2012_12_11_erekson_201648_sdc1.pdf

This is a link to a “Vaginal Symptoms Questionnaire” from the British Society of Urogynaecology: https://bsug.org.uk/budcms/includes/kcfinder/upload/files/useful-docs/ICIQ-VS-Questionnaire.pdf

The “Day-to-Day Impact of Vaginal Aging Questionnaire” asks more about the emotional impacts of GSM symptoms than the “Vulvovaginal Symptoms Questionnaire” and explores how they are affecting one’s relationship with oneself.

Information about the questionnaire: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Day-to-Day_Impact_of_Vaginal_Aging_Questionnaire

The questionnaire itself: https://www.ashasexualhealth.org/pdfs/DIVA.pdf

The “Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)” asks about sexual functioning, frequency, and satisfaction: https://www.apta.org/contentassets/a10dbafd45234c7a98ae3dd98385cdab/fsfi_test.pdf

The “Menopause-specific Quality of Life (MENQOL) Questionnaire” asks about a range of menopause symptoms, some of which have to do with GSM. This link takes you to the MENQOL and the “Menopause Symptoms Treatment Satisfaction (MS-TSQ) Questionnaire”: https://cdn-links.lww.com/permalink/meno/a/meno_21_8_2013_10_30_bushmakin_meno-d-13-00245_sdc1.pdf

You can score some of these questionnaires yourself, however I have included them primarily so that you can

· Learn about the variety symptoms involved in GSM and see which may be affecting you

· Get a sense of how severely symptoms are impacting your life

· Have a material tool you can take to your provider(s) to help you start a conversation and enable you to point to specific issues that need to be addressed

"Menopause Matters," a menopause education group in the UK, also has a simple “vaginal symptoms” checklist you can fill out to take to your doctor: https://www.menopausematters.co.uk/pdf/VAchecklist.pdf

Treating GSM

Part of what is so frustrating about the ignorance and shame surrounding GSM is that treatments are typically simple, effective, and safe.

Lubricants and moisturizers

Because vaginal dryness is such a common complaint, and because these solutions are somewhat familiar and feel low risk to most practitioners, lubricants and moisturizers tend to be what is recommended first. Indeed, the 2014 NAMS statement “recommends vaginal lubricants and moisturizers as the first line of treatment” (Doust et al., 2023). Unfortunately, doctors and women tend not to be educated about the pros and cons of vaginal lubes and moisturizers.

Dr. Jen Gunter, in her book The Menopause Manifesto, has 4 important pages dedicated to discussing vulvar care, lubricants, and moisturizers. I highly recommend checking out her book.

Lubricants are typically used during sex. There are three types of lubricant: water-based, silicone-based, and oil-based.

Critical things to consider:

· Oil-based lubricants are not compatible with latex condoms!

· pH or acidity in the lubricant. Healthy vaginal pH is 3.5-4.5. It tends to increase during menopause, which is part of what creates irritation and increases the risk of infection in GSM. You want to choose a lube that is as close to a healthy vaginal pH as possible. Frustratingly, most lubricants don’t list their pH.

· Osmolality. Osmolality has to do with the concentration of a solution. Gunter says, “When the osmolality [of a product] is higher than that of vaginal secretions the product will draw water out of the vaginal tissues…” This increases the risk of irritation and infection. It’s best to use a lubricant with <380 mOsm/kg and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends against lubricants with >1,200 mOsm/kg.

· Preservatives: Avoid products with clorhexidene gluconate, polyquaternium, and >8.3% glycerin. They can damage vaginal microbiota.

Stabile et al. (2023) warn that several ingredients in vaginal lubricants, “including glycerin, parabens, sorbic acid and chlorhexidine gluconate…all have been shown to have antimicrobial properties” and inhibit the growth of vaginal Lactobacillus (p.354).

· Warming products or using lubricants with flavoring or fragrances should be avoided.

Some women have great success using coconut or olive oil as a lubricant for sex.

Hyaluronic acid, a lubricant “with ionic properties that attract water to increase tissue volume and epithelial integrity” was shown in several low to high quality studies to be almost as effective as vaginal estrogen in improving “vaginal pH, subjective symptoms of atrophy, and dyspareunia” (Evans et al., 2023). It is not necessarily used specifically for sex, but may be used to address general symptoms of dryness.

Moisturizers aim to rehydrate vaginal tissues and “are formulated to be bioadhesive, so the product stays on the vaginal tissues and lasts for several days” (p.169). They can be water-, silicone-, oil-, or hyaluronic acid-based.

Moisturizers do need to be used regularly, and if one type doesn’t work after a few weeks trying another one may do the trick.

One systematic review looked at studies using Replens, a ‘polycarbophil-based vaginal moisturizer” that “produces a moist film over the vaginal tissue, which remains attached to the epithelial cell surface.” Evans et al. (2023) found that Replens improved vaginal pH, dryness, and dyspareunia. It generally performed better than placebo and sometimes equal to estrogen in moderate to high quality studies. There were no adverse effects reported.

Vaginal estrogen

The gold standard treatment for GSM symptoms is vaginal estrogen. This is applied locally, directly to the vagina, via cream, suppository, or a ring that can be inserted once every few months. Vaginal estrogen is usually given in low doses, and because its effects are local and it typically does not get absorbed into the bloodstream, it is generally considered safe even for those women who have or have had cancer.

Having said this, it is clear from my research that there is still a lot of confusion and concern about whether or not vaginal estrogen is, in fact, safe for some women, particularly those with hormone receptive cancers. In an attempt to address these concerns, a group of researchers in Spain conducted a study using an “ultra-low-dose 0.005% estriol vaginal gel.” Not only did the dosage offer “a 10-fold reduction in estrogen use compared to other GSM treatments,” but estriol is a weaker form of estrogen than estradiol, which is the form of estrogen typically used in hormone therapy (Fernandez et al., 2024).

Results of this study showed a significant decrease in rate of UTIs, reduction in episodes of asymptomatic bacteriuria, and improved vaginal pH. Authors also noted that the estriol was encased in a highly moisturizing compound that they surmise may have offered additional benefits by moisturizing and lubricating the vulvovaginal area, “reducing the risk of small lesions and micro abrasions that facilitate the entry of infection-causing bacteria” (p.5).

Systemic estrogen

Interestingly, the systemic estrogen (pills, patches, or creams) typically used in menopause hormone therapy (MHT) usually fails to improve GSM symptoms because estrogen levels in the vulvovaginal region do not rise high enough to help (Angelou et al., 2020; Fernandez et al., 2024; Gunter, 2021). In fact, systemic estrogen has been implicated in making the urinary symptoms of GSM worse (Doust et al., 2023)!

Hormonal alternatives to estrogen for GSM

Apart from cancer or other hormone sensitive conditions, some women are simply not comfortable with the idea of using estrogen or hormones to treat GSM or menopause symptoms. There are several options that can be effective in lieu of estrogen.

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is a precursor to other hormones, specifically estrogen and androgens, including testosterone. Topical DHEA can be used locally in the vagina and has been shown to improve vaginal pH and dryness, dyspareunia, and sexual function over placebo in several moderate to high quality studies (Evans et al., 2023).

Both DHEA and vaginal estrogen can take up to three months to take full effect, though some results can often be felt sooner.

Like estrogen or DHEA, testosterone can be administered topically to the vagina. Testosterone “induces proliferation of the vaginal epithelium,” which can help prevent infection. In moderate to high quality studies, it was found that testosterone “may improve objective signs of atrophy, vaginal dryness, and possibly sexual function” (Evans et al., 2023).

Pharmaceutical options for GSM

Ospemifene is a pill, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that acts like an estrogen on some tissues, but not on others. Ospemifene interacts with estrogen receptors in the vaginal wall to increase thickness and reduce pain associated with dyspareunia. It was shown to lower vaginal pH, improve sexual function, and decrease urinary problems. However, it also tends to increase vasomotor symptoms, endometrial thickness, and candidiasis over placebo (Evans et al. 2023).

Endometrial thickening can be an indication of disease and/or a precancerous condition in the tissues of the endometrium. According to Gunter, “ospemifene acts like an estrogen on the uterus” (p.173). Because of this, progesterone may be needed to counteract these effects and protect the lining of the uterus just as in systemic menopause hormone therapy (MHT). However, at this point there is not enough data to draw a conclusion, and Gunter suggests that this decision, like all treatment decisions, should be individualized.

Tibolone is not approved for use in the United States but is used in other countries as hormone replacement therapy and to treat osteoporosis and endometriosis. In low to moderate quality studies, it was found to improve vaginal dryness, atrophy, and dyspareunia, as well as urinary urgency and incontinence (Evans et al., 2023).

Lidocaine can be used before engaging in penetrative sex to help provide pain relief. This has been studied in breast cancer survivors and “90% of patients reported comfortable intercourse” (Angelou et al., 2020). Lidocaine can be purchased over the counter, but if you are going to use it vaginally, please discuss it with your doctor first so that you can get the correct dosage and application type.

Costs of all lubricants, moisturizers, hormones, and pills are likely to vary based on insurance, type of carrier (cream, suppository, ring, etc.), geographic region, dosage, and frequency of use.

Hormone-free, non-pharmaceutical treatments for GSM

Pelvic floor physical therapy is a non-invasive option that can be especially beneficial for any symptoms having to do with urinary urgency or incontinence, prolapse, or atrophy (muscular degeneration). In other nations, pelvic floor PT is typically offered to women after giving birth and is viewed as a critical part of healthcare for women’s physical, sexual, and emotional well-being.

Energy-based therapies

There are two types of lasers being used to address symptoms of GSM. Although both are approved for use in certain dermatological applications like skin resurfacing and scar treatment, they are being used off-label to stimulate collagen remodeling, increase blood flow, and stimulate epithelial and microbiota regeneration in the vagina. They do this by using heat and creating small wounds in the tissue to promote the growth of “thickened, glycogen-rich and well-vascularized” vaginal tissue (Evans et al., 2023; Kaunitz et al., 2019).

Microablative fractional CO2 laser: In moderate quality studies comparing this laser with estrogen, they performed about evenly, with some studies favoring estrogen for improved sexual function, subjective atrophy symptoms, increased vaginal health, and decreased urinary symptoms, and others favoring laser. In studies that compared the CO2 laser with a sham laser, the CO2 laser outperformed the sham laser in decreases in dyspareunia and dysuria and was equal to sham in subjective dryness and symptoms of atrophy. In those studies that looked at adverse events and pain associated with the laser procedure, “no significant problems” were found (Evans et al., 2023).

In a study done by Athanasiou et al. (2016) fifty-three postmenopausal women received intravaginal laser therapy once a month for three months. The results of this study were impressive. At the end of the protocol:

· Vaginal pH decreased significantly in 89% of participants, with 32% attaining a pH of <4.5 (normal is 3.5-4.5).

· There was a “significant progressive increase of Lactobacillus morphotypes observed” (p.3). This was especially notable because at baseline, 15% of participants had a “complete absence of any vaginal flora” (p.3, italics mine).

· “Normal vaginal epithelial cells significantly increased after the second and third therapies compared to baseline” (p.3).

· Of 16 participants who were not sexually active at baseline due to GSM symptoms, 15 resumed sexual activity after treatment.

Apart from temporary mild irritation of the vaginal entrance, which spontaneously resolved after a couple of hours, no adverse effects were noted.

Erbium laser

Although in their systematic review of the literature, Evans et al. (2023) found that the erbium laser was effective in improving vaginal pH, dryness, and dyspareunia, the quality of the studies was low. In those studies monitoring for complications, none were reported.

Safety

In July 2018 the FDA release an “FDA Safety Communication” alerting consumers to “serious adverse events” connected to the use of “energy-based devices (radiofrequency or laser) which were approved to treat gynecologic conditions but being used for vaginal procedures.” The FDA went on to clarify that lasers had not been cleared for use in treating any symptoms related to menopause or GSM (Kaunitz et al., 2019).

This communication was likely in response to an April 2019 article in the journal Menopause, which featured four case studies of women who had experienced vaginal lacerations, post-treatment dyspareunia, stenosis, or scar tissue after laser use (Gordon et al., 2019).

However, in the same journal in October 2020, Guo et al. published the results of a systematic review investigating whether the available evidence about lasers supported the FDA’s safety communiqué. They concluded that “Lacking strong evidence indicating significant patient risk for vaginal laser treatment of GSM, the FDA safety communication appears unsubstantiated and implies gender bias” (Guo et al., 2020).

Because the use of lasers to treat GSM symptoms is off-label at this point, I think it is wise to proceed with caution. While there are reputable medical institutions offering laser for the alleviation of GSM symptoms, there are also likely to be people promoting this service who do not have the medical and technological knowledge to safely use lasers in the vaginal region.

Laser treatment is unlikely to be covered by insurance and can cost from $500 to $1,000 per session. Multiple sessions usually need to be done and then may need to be refreshed each year. Here is a link to the Cleveland Clinic’s page on their laser therapy, MonaLisa Touch: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/24779-monalisa-touch

Probiotics

The Vaginal Microbiome

I was amazed reading about the importance of the vaginal microbiome and shocked to learn that “In the vaginal microbiota of premenopausal women, Lactobacillus species constituted approximately 71.98%, and pathogenic flora constituted approximately 16.87%. They were 10.08% and 26.78%, respectively, in the vaginal microbiota of postmenopausal women (Yoshikata et al., 2021, italics mine). What I find particularly discouraging is that not only do the numbers of beneficial bacteria decline during menopause, but detrimental bacteria multiply and flourish in the new environment created by estrogen decline (Stabile et al. 2023). Estrogen promotes the production of glycogen, which is a substrate for Lactobacilli. Additionally, as the epithelium (the lining) of the vagina becomes compromised, so does the living space for Lactobacilli.

Although it is not fully known whether Lactobacilli “promote vaginal health or whether they are a marker for vaginal health” (Stabile et al., 2023), what is known is that they are important in defending the vagina against infections of various types and colonization by pathogenic bacteria and “the ideal vaginal environment is maintained by Lactobacillus species” (Yoshikata et al., 2021).

A 2022 study conducted by Yoshikata et al. and described in Stabile et al. (2023) found that using feminine products containing Lactobacillus improved the vaginal ecosystem and urogenital health.

Multiple studies have shown that oral ingestion of probiotics can lead to menopausal symptom relief. In a 12-week, multicenter, randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Korea, it was “reported that oral ingestion of Lactobacilli by postmenopausal women significantly improved symptoms related to menopause” (Stabile et al., 2023). It’s important to note that this article does not describe which specific menopausal symptoms a couple of these studies are targeting, though one was looking particularly at GSM issues.

Yoshikata et al. (2021) found that there does seem to be “crosstalk” between the gut microbiome and vaginal flora. “Therefore, dietary habits and measures to improve the gut environment by increasing the Lactobacillus population in the gut might increase the population of Lactobacillus and reduce that of the bacterial flora in the vagina.”

Oral probiotics geared toward women, and specifically vaginal health, may be helpful in treating GSM symptoms.

Sex

Angelou et al. (2020) note that maintaining regular sexual activity can help maintain vaginal elasticity and lubricative response.

Last thoughts

If this all seems like an unending parade of possibility and nuisance, I completely understand. Genitourinary symptoms arose for me several months ago, a few years into my perimenopausal symptoms odyssey. First, I used Kindra, a water-based moisturizer with glycerin that was initially effective in alleviating the dryness, although knowing what I know now I will seek out a moisturizer with hyaluronic acid and try that. While the moisturizer worked for a while, the symptoms kept piling up, shifting from dryness and irritation to pain with sex, lack of lubrication, and then nocturia (having to pee a lot in the middle of the night).

I started on vaginal estrogen, and it has been extremely beneficial. However, I have begun to have some spotting that comes around every 10 days or so for 1-3 days at a time. I had an ultrasound to rule out any problems with my endometrium and there are none. Now I’m considering asking my doctor for vaginal DHEA to see if that makes a difference in the spotting as well as keeping the symptoms at bay.

It's a journey.

There is a lot more to say about the health and welfare of the urinary tract and bladder in postmenopause and as we age, especially because recurrent UTIs have been associated with increased dementia risk, sepsis, and death in older women (Muir, 2023). Pelvic health generally and pelvic floor health specifically are also critical to consider, and I will dedicate future posts to these topics.

Although vaginal dryness may not be a big deal for some people, what is clear to me after all the research I have done is that there is a lot happening in the pelvic and genital regions that we cannot see and that we might not feel the effects of until much later. There is, as I said above, a profound physical and biochemical remodeling going on and it is important to be aware and stay attentive in order to cultivate and maintain vulvovaginal, urinary and bladder, sexual, mental, and emotional health going forward.

Resources

Angelou K, Grigoriadis T, Diakosavvas M, et al. (April 08, 2020) The Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: An Overview of the Recent Data. Cureus 12(4): e7586. DOI 10.7759/cureus.7586

Athanasiou, S., Pitsouni, E., Antonopoulou, S., Zacharakis, D., Salvatore, S., Falagas, M. E., & Grigoriadis, T. (2016). The effect of microablative fractional CO2 laser on vaginal flora of postmenopausal women. Climacteric, 19(5), 512-518. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2016.1212006

Doust, J., Huguenin, A., & Hickey, M. (2024). Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: Does Everyone Have It?. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 67(1), 4-12. DOI: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000834

Evans, E. A. C., Hobson, D. T., Aschkenazi, S. O., Alas, A. N., Balgobin, S., Balk, E. M., ... & Rahn, D. D. (2023). Nonestrogen therapies for treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 142(3), 555-570. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005288

Fernández, N. M., Salamanca, J. I. M., de Quevedo, J. I. P. G., Morales, M. P. D., Alameda, L. P., Tello, S. D., ... & Aguilar, E. G. (2024). Efficacy and safety of an ultra-low-dose 0.005% estriol vaginal gel in the prevention of urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Maturitas, 190, 108128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2024.108128

Gordon, C., Gonzales, S., & Krychman, M. L. (2019). Rethinking the techno vagina: a case series of patient complications following vaginal laser treatment for atrophy. Menopause, 26(4), 423-427. DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001293

Gunter, Jen. (2021). The Menopause Manifesto. Citadel Press.

Guo, J. Z., Souders, C., McClelland, L., Anger, J. T., Scott, V. C., Eilber, K. S., & Ackerman, A. L. (2020). Vaginal laser treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: does the evidence support the FDA safety communication?. Menopause, 27(10), 1177-1184. DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001577

Hudson, P. (2025, February 16). The unspoken agony of vaginal dryness: ‘I had to give up four jobs in four years.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/feb/16/the-unspoken-agony-of-vaginal-dryness-i-had-to-give-up-four-jobs-in-four-years

Kaunitz, A. M., Pinkerton, J. V., & Manson, J. E. (2019). Women harmed by vaginal laser for treatment of GSM—the latest casualties of fear and confusion surrounding hormone therapy. Menopause, 26(4), 338-340. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001313.

Mitchell, C. M., Larson, J. C., Reed, S. D., & Guthrie, K. A. (2023). The complexity of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: number, severity, and frequency of vulvovaginal discomfort symptoms in women enrolled in a randomized trial evaluating treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Menopause, 30(8), 791-797. DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002212

Muir, K. (2023, December 17). ‘Millions of women are suffering who don’t have to’: Why it’s time to end the misery of UTIs. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/dec/17/millions-of-women-are-suffering-who-dont-have-to-why-its-time-to-end-the-misery-of-utis

Nappi, R. E., & Kokot-Kierepa, M. (2010). Women's voices in the menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas, 67(3), 233-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.08.001

Stabile, G., Topouzova, G. A., & De Seta, F. (2023). The role of microbiota in the management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Climacteric, 26(4), 353-360. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2023.2223923

Vaginal Maturation Index: https://myvagina.com/the-vaginal-maturation-index/

Yoshikata, R., Yamaguchi, M., Mase, Y., Tatsuzuki, A., Myint, K. Z. Y., & Ohta, H. (2022). Age-related changes, influencing factors, and crosstalk between vaginal and gut microbiota: a cross-sectional comparative study of pre-and postmenopausal women. Journal of Women's Health, 31(12), 1763-1772. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2022.0114

Yoshikata, R., Yamaguchi, M., Mase, Y., Tatsuyuki, A., Myint, K. Z. Y., & Ohta, H. (2022). Evaluation of the efficacy of Lactobacillus-containing feminine hygiene products on vaginal microbiome and genitourinary symptoms in pre-and postmenopausal women: A pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS One, 17(12), e0270242. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270242

Image References

Black Iris: https://www.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2014/february/05/what-do-you-see-in-georgia-okeeffes-flowers/