Diagnosing Osteoporosis

As mentioned in the previous post, osteoporosis is referred to as “the silent disease” because most people don’t know they have it until they have suffered a fragility fracture. Depending on a person’s age when this fracture happens, the amount of bone loss that may already have taken place throughout the body could be significant.

For the layperson, low bone mass and low bone mineral density (BMD) essentially refer to the same thing, a reduction in the structural integrity of bone and increased vulnerability to fracture and deterioration. Therefore, I will use the terms interchangeably.

There are a few different methods for screening for low bone mass, as well as some self-assessment tools that can be used by an individual and/or their doctor to determine if a screening seems to be warranted.

Self (or Assisted)Assessment

The two primary self-assessment tools are the Osteopathic Self-Assessment Tool (OST) and the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX).

OST

The OST was developed by Dr. Leonard Koh, an Asian doctor from Singapore, and, because it is based on Asian populations, may not be as applicable to other people groups. Additionally, it uses only current age and weight to determine risk of osteoporosis. This leaves out multiple risk/protective factors such as family history, lifestyle, and personal medical history.

This is a link to an OST at the National Library of Medicine:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45516/figure/ch10.f2/

It is obviously quite reductionistic and is typically used to figure out how much of a priority it is for an individual to get screening for osteoporosis.

FRAX

The FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment Tool) is a bit more detailed. While it can be used for self-assessment, it does ask about BMD in the femoral neck and may be most useful when one has a health professional to help interpret results.

https://frax.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=9

To be clear, the FRAX assesses fracture risk, NOT how likely it is that an individual may have osteoporosis. It involves answering a list of questions that includes information about risk factors, family history, age, and weight. Without a current BMD value for the femoral neck, it may not give as accurate a risk assessment as it would if that information was available (JAMA, p.E3). However, according to Silverman & Calderon (2010), the FRAX can be helpful for clinicians seeking to determine who among their patients needs further osteoporosis screening and treatment and who does not.

Even so, they also point to several limitations of the FRAX:

· The FRAX tool was developed in Scotland and, as with the OST, it may not be as useful in working with certain racial and ethnic groups. According to the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF), there are country-specific versions of FRAX available. However, they go on to say that, “race-specific calculators (eg, FRAX) that use fixed fracture risk treatment thresholds not specific to [non-White] race and ethnicity may be less likely to identify Asian, Black, and Hispanic persons as high risk” (USPSTF, p.E5, italics mine) and treat accordingly.

· FRAX does not inquire or gather details about a majority of risk factors known to be relevant to the development of osteoporosis.

· In drawing its conclusions, the FRAX does not take into account dose-response relationships with regard to different factors such as alcohol intake or medication use. This means that the FRAX asks for a simple yes or no with regard to medication and alcohol use but does not ask for details about dosages taken or amounts ingested.

· It does not adequately define “secondary osteoporosis”

· It assumes that the relationship between BMI and mortality, as well as the variability in fracture rates, is the same for all racial/ethnic groups

· The data the FRAX calculator uses to determine fracture risk needs to be updated. According to the 2025 USPSTF recommendation statement, the FRAX uses “cohort studies that are 30 to 40 years old to estimate race-specific fracture incidence, [and] mortality estimates that have not been updated since 2004” (JAMA, p.E3-4).

Other assessment instruments that have been studied include:

· The Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI), which evaluates a woman's risk of having osteoporosis based on her age, weight, and estrogen use.

· The Simple Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE) uses age, weight, race, rheumatoid arthritis, history of non-traumatic fracture over age 45, and estrogen use to estimate the risk of a person developing osteoporosis.

Both of these instruments are used to guide healthcare professionals in determining whether or not further screening is warranted.

Medical Screening

There is not a lot of research on potential harms stemming from osteoporosis screening processes. What we do know is that, apart from ultrasonography, they all involve some radiation in order to create the images that are evaluated.

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA)

The DXA (pronounced “dexa”) is the most commonly used scan to determine bone mineral density (BMD). The DXA uses radiation to measure how much calcium and other minerals are in a specific area of bone, usually the femoral neck and head and the lumbar spine (McGonigle, webinar).

Pros of the DXA scan:

· Results tend to correlate with bone strength and clinical fracture outcomes (JAMA, p.E3), i.e., it is frequently correct about an individual’s bone mass status.

· It uses low doses of radiation.

· It is fairly easy to find a location and access the scan if you have a relationship with a medical health professional.

· Many insurance companies cover this test.

Cons of DXA:

· While it can look at the quantities of various minerals in the bone, DXA cannot determine the quality or the microarchitecture of the bone, nor can it tell us how much bone turnover (creation and destruction) is happening.

· The DXA scan typically only looks at the upper femur and lumbar spine. However, the thoracic spine (the part that runs through the rib cage), is specifically vulnerable to osteoporotic damage. In fact, vertebral compression fractures are the most common osteoporotic fractures (Walker & Shane, p.1980). These types of fractures are what cause height loss and kyphotic curvatures, (sexist-ly known as “Dowager’s humps), in those with severe osteoporosis.

· Those persons with smaller statures and bones are more likely to have lower scores coming out of their DXA scans even though their bone quality might be good.

· Readings can vary between machines and technicians reading the scans.

Trabecular Bone Score (TBS)

Trabecular bone tissue is the network of hard and soft tissues that honeycomb the insides of the bones and give them their structural integrity. The TBS is derived by using the lumbar spine image from a DXA scan and running it through software designed to discern the trabecular architecture of the bone. This information can help discern the quality of the bone and predict fracture risk independent of BMD.

While the TBS offers a more detailed look at what is happening inside the bone, the TBS relies on DXA images and so does not reveal anything about what might be happening in the thoracic spine. It is also not regularly prescribed or used by doctors and may not be covered by insurance.

Quantitative Computed Tomography scan (CT)

CT scans may be used in specific cases to more accurately measure trabecular bone density than DXA can. However, CT scans are rarely used because they are more expensive and more difficult to access, they use higher doses of radiation, and there is poor quality control due to the need to consistently recalibrate the scanners for each measurement (Pavone et al., p.2).

Ultrasonography with FRAX

Ultrasonography used in tandem with the FRAX calculator is best used to determine if more detailed scanning is recommended. It cannot be used to diagnose osteoporosis, but it can help to predict fracture risk. Other benefits: Ultrasound is inexpensive, portable, and does not use radiation, which makes it both accessible and useful for health education

Drawbacks include:

· This technique can give an estimate of bone mineral density, but not a measurement.

· As with any of the scans, results may differ depending on machines and technicians.

· The T-scores obtained from ultrasonography are different from the DXA T-scores and so cannot be used with the World Health Organization (WHO) classification for diagnosing osteoporosis (Lewiecki et al., 2006).

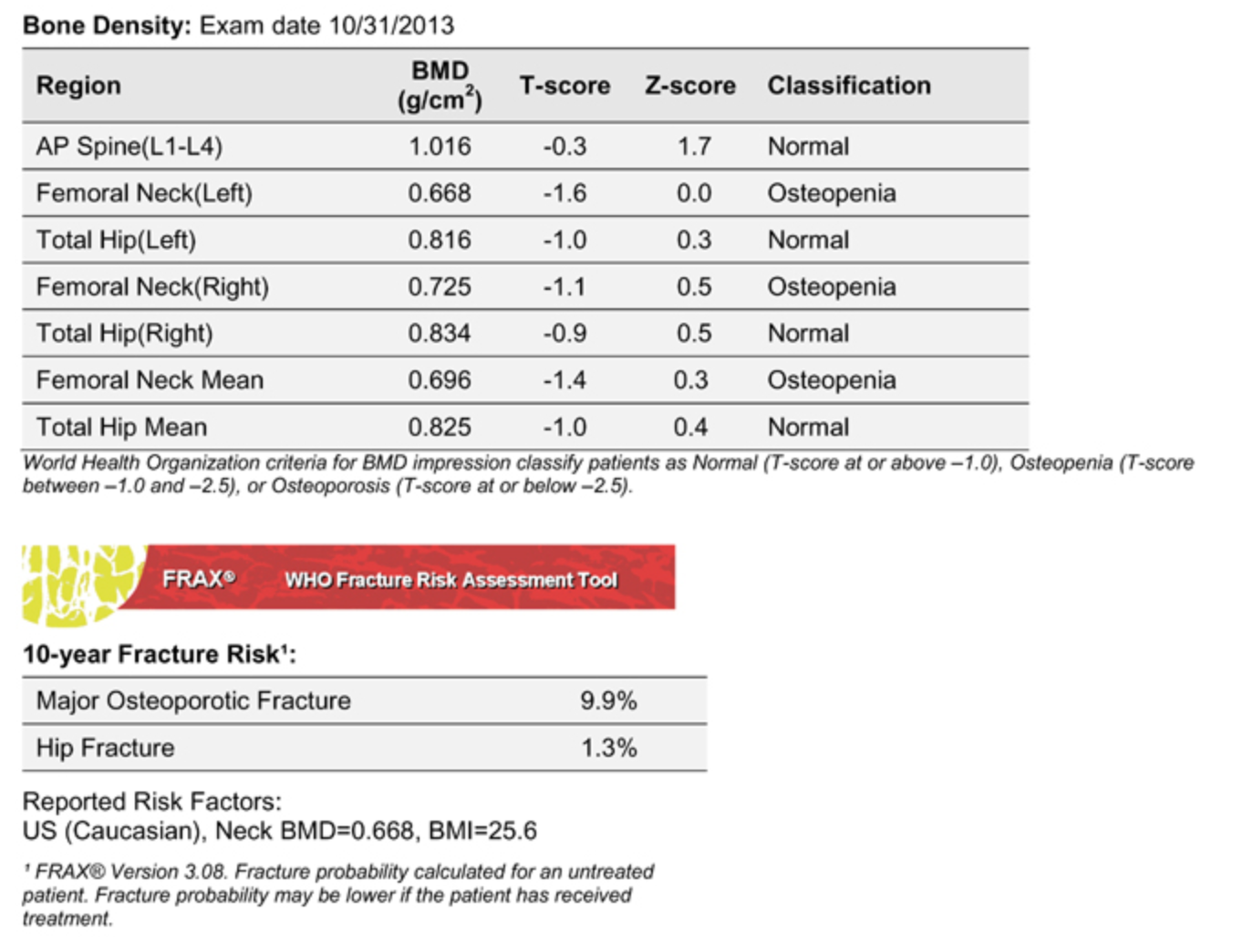

T-scores and Z-scores: How to Read a DXA scan

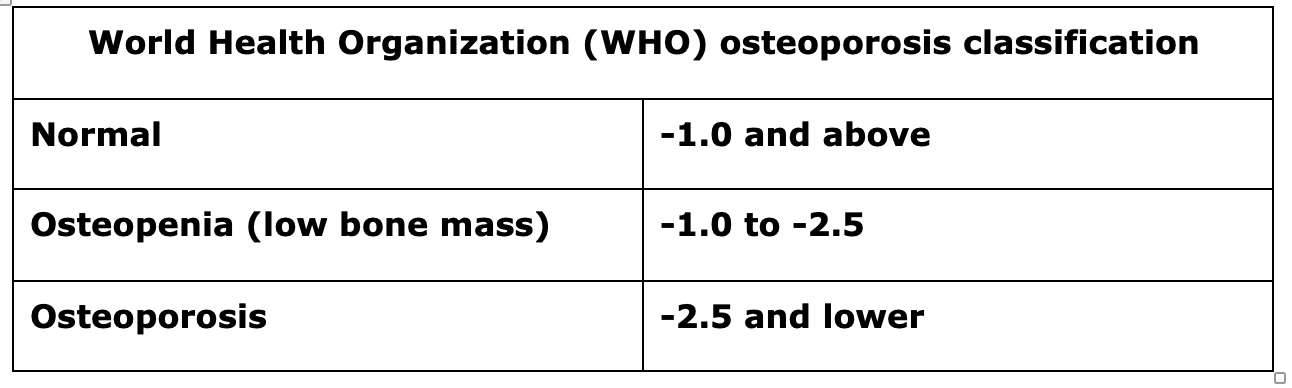

T-scores are used to assess bone density in peri- and postmenopausal women, and men 50 years and older.

Reading one’s DXA scan results can be confusing and frustrating. Every time I revisit mine, I have to re-learn what it all means. It doesn’t help that the scores are listed entirely as negative numbers. (It does this because the scan is looking for bone loss not bone gain, which would be listed in positive numbers.)

Essentially, the T-score is the difference between your bone mineral density and 0. "Zero" is the bone mineral density of a healthy young adult. So in a T-score, your bone is being compared to that of a healthy adult in their twenties.

Each number in a T-score is one or one-half of a standard deviation (SD) away from 0. So -1.0 is one SD from 0 and -2.5 is two and one-half (SDs) from 0. According to Walker & Shane (2023), "Each standard deviation reduction below a T score of 0 is associated with a doubling or tripling in the risk of fracture" (p.1979-80).

The T-score is the score your doctors will be focusing on because they want to see what the difference is between your bone now and the bone you (ideally) had 30-55 years ago.

Z-scores add to the confusion of attempting to read DXA results and are not used to diagnose peri- and postmenopausal people. Z-scores are used to assess BMD for premenopausal women and men under age 50.

Essentially, Z-scores compare an individual’s bone density to the bone density of one’s peers (similar in age and often in gender and ethnicity). So a Z-score of -2.0 or lower is “below expected range for age,” and a Z-score higher than -2.0 is “within expected range for age.”

Here’s an example you can practice deciphering:

Who should get scanned & when?

Health professionals—specifically nurse practitioners—started offering me the DXA scan when I turned 50. I was confused about this because I had in my head that women didn’t need to start worrying about scanning for bone loss until they were in their 60s. When I asked them why they thought I might need one their response across the board was, “It’s good to have a baseline.”

At no point did anyone do any formal preliminary screening with me to see what my fracture risk or odds of having osteoporosis were. And no one ever told me that my bone loss had already started to happen in my thirties, or that the time of most rapid bone loss starts about one year prior to the final menstrual period (Gunter, p.133).

In a 2017 systematic review by Pavone et al., the recommendation emerging from another review, "Trends and Disparities in Osteoporosis Screening Among Women in the United States, 2008-2014" (Gillespie & Morin, 2017), was that "Patients should be prescreened starting at 50 years of age to maximize the benefit of fracture prevention" (p.2, italics mine).

At the time I turned 50 in 2021, I was not being disturbed by any perimenopausal symptoms. I could feel things changing inside, but for the most part I was ticking along as I had been for years. Although my mother has osteoporosis, and my paternal grandmother almost died in the aftermath of a hip fracture she sustained, I have no risk factors apart from this family history. I was active and healthy and imagined that osteoporosis probably wouldn’t apply to me for a long time. This was an assumption grounded in a rather profound ignorance about both menopause and osteoporosis. I had no idea that just by being a woman in peri- and postmenopause my risk of osteoporosis and fracture skyrocketed.

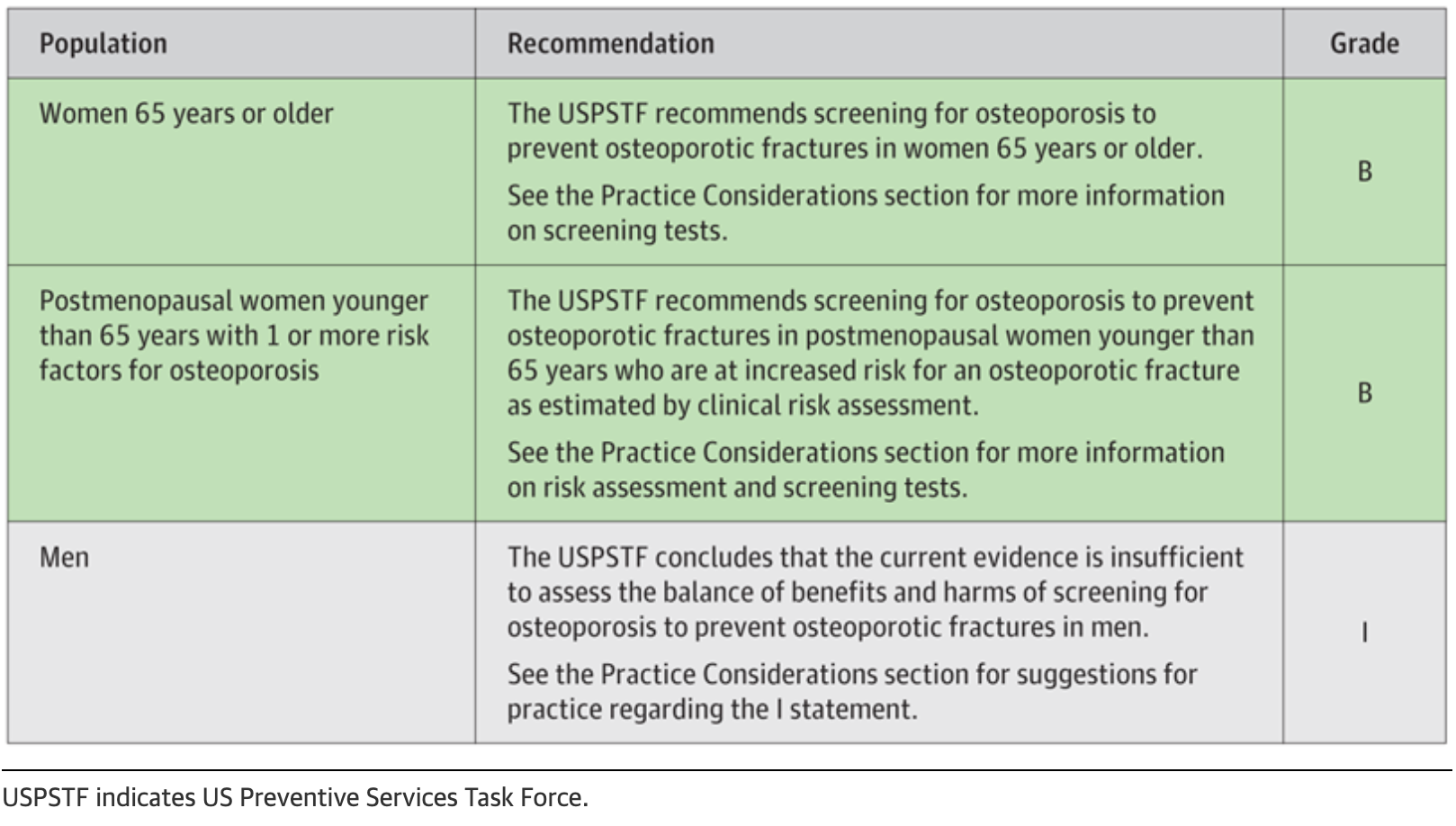

The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) is an independent panel of experts who review data in an ongoing way to make evidence-based recommendations about preventative testing and screening. The 2025 USPSTF Recommendation Statement, “Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures,” advises this:

As you can see, it is recommended that women with even one risk factor be screened for osteoporosis even if they are younger than 65 years. Of course, women have to know what the risk factors for osteoporosis are in order to assess whether or not to get scanned. They also have to know enough about this disease process and its progression to appreciate the importance of prioritizing prevention and treatment.

Keep in mind that this recommendation statement is oriented explicitly toward screening “for preventing fractures,” and not for discovering and preventing the progression of osteoporosis.

The majority of health professionals in Western medicine are oriented toward preventing and treating catastrophic outcomes. Screening in the service of a proactive approach to prevention—or even potential reversal—of disease is decidedly not mainstream. The average age of attaining menopause in most Western nations is 51 years. If a woman is not offered, or does not accept the offer of, a DXA scan until she is already postmenopausal, the accelerated bone loss of the perimenopausal transition will be complete. At this point, it is more likely that she will be diagnosed with osteoporosis rather than osteopenia, and it will be that much more difficult for her to halt or reverse the bone loss that has happened.

When I finally agreed to a DXA scan, just before my 53rd birthday, it revealed that I had osteopenia in my lumbar spine and the numbers were close to the line that demarcates osteopenia from osteoporosis. It was a sucky birthday gift and threw me into gloom for a bit. Overall, though, I feel fortunate I didn’t wait any longer to get the scan. I have an opportunity now to try to prevent further bone loss and reverse the loss that has already taken place.

In the next two posts we will explore pharmacological and lifestyle interventions for osteoporosis.

Resources:

Gillespie, C.W., & Morin, P.E. (2017). Trends and disparities in osteoporosis screening among women in the United States, 2008-2014. American Journal of Medicine, 130, 306-316. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.10.018

Gunter, Jen. The Menopause Manifesto.

Lewiecki, E.M., Richmond, B., & Miller, P.D. (2006, August). Uses and misuses of quantitative ultrasonography in managing osteoporosis. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 73(8), 742-752. https://www.ccjm.org/content/ccjom/73/8/742.full.pdf

McGonigle, Andrew. Webinar: "Debunking Bone Health" (You cannot access the webinar, but you can find Dr. McGonigle at https://www.doctor-yogi.com/

Pavone, V., Testa, G., Giardina, S.M.C., Vescio, A., Restivo, D.A., & Sessa, G. (2017, November). Pharmacological therapy of osteoporosis: A systematic current review of literature. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 8(803), 1-7. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00803

Silverman, S.L., & Calderon, A.D. (2010, December). The utility and limitations of FRAX: A US perspective. Current Osteoporosis Reports, 8(4),192-7. DOI: 10.1007/s11914-010-0032-1

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2025;333(6):498–508. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.27154

Walker, M.D., & Shane, E.S. (2023). Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. New England Journal of Medicine, 389: 1979-1991. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMcp23073

Images:

Bone density report: https://www.avoidboneloss.com/hologic.htm

DXA scan: https://www.healthline.com/health/bone-density-scan-results-if-you-are-younger

T-score & Z-scores: https://www.cover-tek.com/interpreting-bone-density-test-results/