Brain Fog

In May 2025, a group of researchers in the UK published an article entitled “Defining brain fog across medical conditions” in an attempt to clarify what brain fog is and where it comes from.

· Are there distinct neurobiological and physiological mechanisms that trigger brain fog?

· Or is brain fog more accurately thought of as a cognitive effect of some behavioral pattern, for example, sleep habits, multitasking, or how we cope with stress?

· Is it, as many perimenopausal women fear, a pernicious precursor of encroaching memory decline and dementia?

Although over two-thirds of perimenopausal women experience brain fog, and research has illustrated specific elements of cognitive impairment in women going through the menopause transition, the reasons why women experience brain fog and how best to address it are, unsurprisingly, not well understood.

Brain fog is a symptom that is poorly understood in most of the illnesses and conditions it is associated with. These include Long Covid, fibromyalgia, lupus, POTS, chronic pain, traumatic brain injury, and chemotherapy treatment, in addition to perimenopause. Trying to get a bead on brain fog is difficult because to do requires investigation into 1) neurological and/or hormonal mechanisms are contributing to it in any given condition, and 2) figuring out how these underlie or overlap with other cognitive-behavioral factors, in particular sleep or depression.

Symptoms of brain fog

Symptoms of brain fog can be cognitive, emotional, and/or somatic and include:

· Distractibility, inability to focus on a task

· ADHD-like behaviors

· Physical and mental fatigue

· Difficulty concentrating and taking things in

· Confusion

· Experiences of “information overload”

· Losing track of words and/or things

· Feeling disorganized in one’s mind, an inability to hold multiple ideas or words in the mind at once and prioritize them

· Forgetting names, intentions, or appointments

· It takes more time and effort to communicate, think, or do things that used to be easier/simpler

· A feeling of being slowed down and/or not making much sense

Work and Brain Fog

Symptoms of brain fog can have a particularly deleterious impact on women’s work lives. Women may find themselves at the height of their careers and suddenly begin to experience poor concentration, spotty memory, and fatigue that make it difficult for them to meet their own expectations, much less the expectations of others, in terms of work demands.

“I was really upset by it, and I was in tears because I couldn’t do my job…It meant a lot to me in terms of my self-worth and self-belief in terms of my job and how I deliver my work because all of a sudden, I can’t” (Participant in Johnson & Ogden, 2025).

In the UK, the Fawcett Society Survey (2022) has found that “10% of women who worked during the menopause had left their job due to symptoms,” an astonishing and disheartening figure.

Experiencing brain fog can be scary and disorienting for many women, in part because we are often so skilled at being organized, verbally and intellectually sharp, and capable of juggling many ideas and activities at once—taking on more on the fly—without letting anything drop. When we suddenly start missing appointments, frantically trying to find the phones that we are holding in our hands, and losing the thread in the middle of a work meeting, we understandably start to fear for our sanity, our brain health, and our future.

Risk factors for brain fog

There are some interesting common threads—physiological, psychological, and social—that are risk factors for experiencing brain fog.

First: Estrogen decline is having an impact on every organ and cell in the body, and the brain is particularly vulnerable. According to Denno et al. (2025), “In menopause, cognitive impairment is thought to relate to reduced brain volume in frontal, hippocampal, and temporal areas via oestrogen depletion…” (p.336).

Second: “Heart health is brain health.” (Maki & Jaff, 2022). Maki & Jaff (2022) note that “frequent VMS (vasomotor symptoms) strongly relate to memory difficulties that persist when controlling for self-reported sleep difficulties and objective sleep” (p.3, italic mine). Gunter (2021) writes that women “who have more vasomotor symptoms are more likely to judge their cognitive performance harshly. Vasomotor symptoms can even prime the brain to be more receptive to negative experiences” (p.152).

VMS often impact sleep quality. Sleep deprivation alone can contribute to cognitive difficulties, however, it is also strongly implicated in the development of anxiety, depression, and greater vulnerability to stress. Additionally, as Spencer (2025) points out, “levels of cortisol—the hormone of stress—increase after a hot sweat, and higher levels of cortisol are also associated with memory impairment.”

Finally, Miller et al. (2019) found that “systolic blood pressure showed an inverse association with performance on auditory attention and working memory, a relationship that was not related to endogenous hormone levels at baseline. These results are consistent with the growing body of evidence for a relationship between increased systolic blood pressure and with both adverse structural changes in the brain and decreased cognition” (p.1076). Maki & Jaff (2022) also noted the link between higher systolic BP and dementia risk.

Although there is no clearly delineated mechanism that is yet understood for how blood pressure, heart health, and estrogen impact the brain and working cognition, it is abundantly clear that one’s cardiovascular health and the severity of one’s perimenopausal VMS are likely to influence one’s risk of experiencing brain fog. This may happen due to interrupted sleep, mood swings, or invisible physiological or genetic changes.

Third: Inflammation

Inflammation is likely to be at the root of most dysfunction in the body, no matter how temporary or chronic. However, perimenopause is considered a time of heightened inflammation—with all the risks that entails—even though it is naturally induced by the decline of protective hormones—estrogen, testosterone, and progesterone.

One way inflammation can impact brain health is through its effects on the cardiovascular system. Interestingly, two articles I read noted that increased permeability in the blood brain barrier (BBB) due to systemic inflammation may contribute to the development of brain fog symptoms. In the case of perimenopause, the “decreased integrity of the blood brain barrier (BBB) [is] in the context of lower estrogen states” (Metcalf et al., 2022).

Fourth: Hippocampus

The hippocampus is the seat of memory and learning in the brain. When estrogen declines, it can have a powerful impact on the hippocampus, likely instigating some of the memory and learning challenges associated with perimenopausal brain fog.

However, what also happens for some women, particularly those with trauma histories, is that memories start swamping us. This can happen even for those women who have simply been too busy to deal with non-traumatic emotional and psychological life events. These memories may be discrete images of distinct events, times, people, and places, or they may arise as emotional states, a jumble of thoughts, images, feelings, and/or sensations that are difficult to link to any particular time period or event.

Metcalf et al. (2022) demonstrated that those women with greater than two adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), as measured by the ACE-Q, have heightened inflammatory markers that negatively impacted their verbal memory performance compared to women with fewer or no ACEs.

The article also refers to two other studies illustrating the relationship between early life stress, increased inflammation, and impaired cognition:

In one, ACE’s “demonstrated deleterious cognitive and inflammatory effects following surgical menopause and during natural menopause transition” (p.2). In the second, inflammatory response to a flu vaccine only related to depression symptoms and cognitive impairment among participants with early life stress (p.5).

Fifth: Social Determinants of Health (SDoH)

Multiple studies have shown that myriad SDoH contribute to the likelihood of both developing cognitive impairments during the menopause transition and also of having those impairments become either permanent or progressive, rather than resolving in postmenopause.

Risk factors include:

· Low socioeconomic status

· Being from a low- or middle-income nation

· Being a woman of color

· Low education level

· Early childhood trauma

· Poor nutrition (in childhood and/or currently)

· Mental health challenges

· Physical health disorders

· Current life stressors

· Occupations or leisure activities with low cognitive demand

Sixth: Sleep

It’s clear that sleep difficulties and fatigue—no matter their cause—contribute to brain fog, especially the exacerbation of brain fog symptoms.

Interestingly, Denno et al. (2025) describe the brain fog experienced as part of chronic fatigue syndrome as “a cognitive subtype of fatigue” (p.334). This description seems particularly apropos to me, as it dovetails with my personal experience of brain fog, which I have always felt to be more of a malaise, or inability to get my brain to kick into gear. It also jives with how some other women have described their brain fog to me.

Prolonged standing and dehydration are other elements that can contribute to brain fog.

Clearly, it’s difficult to map out a clear cause and effect for the development of brain fog in perimenopause, as there are so many factors that potentially intertwine and amplify each other.

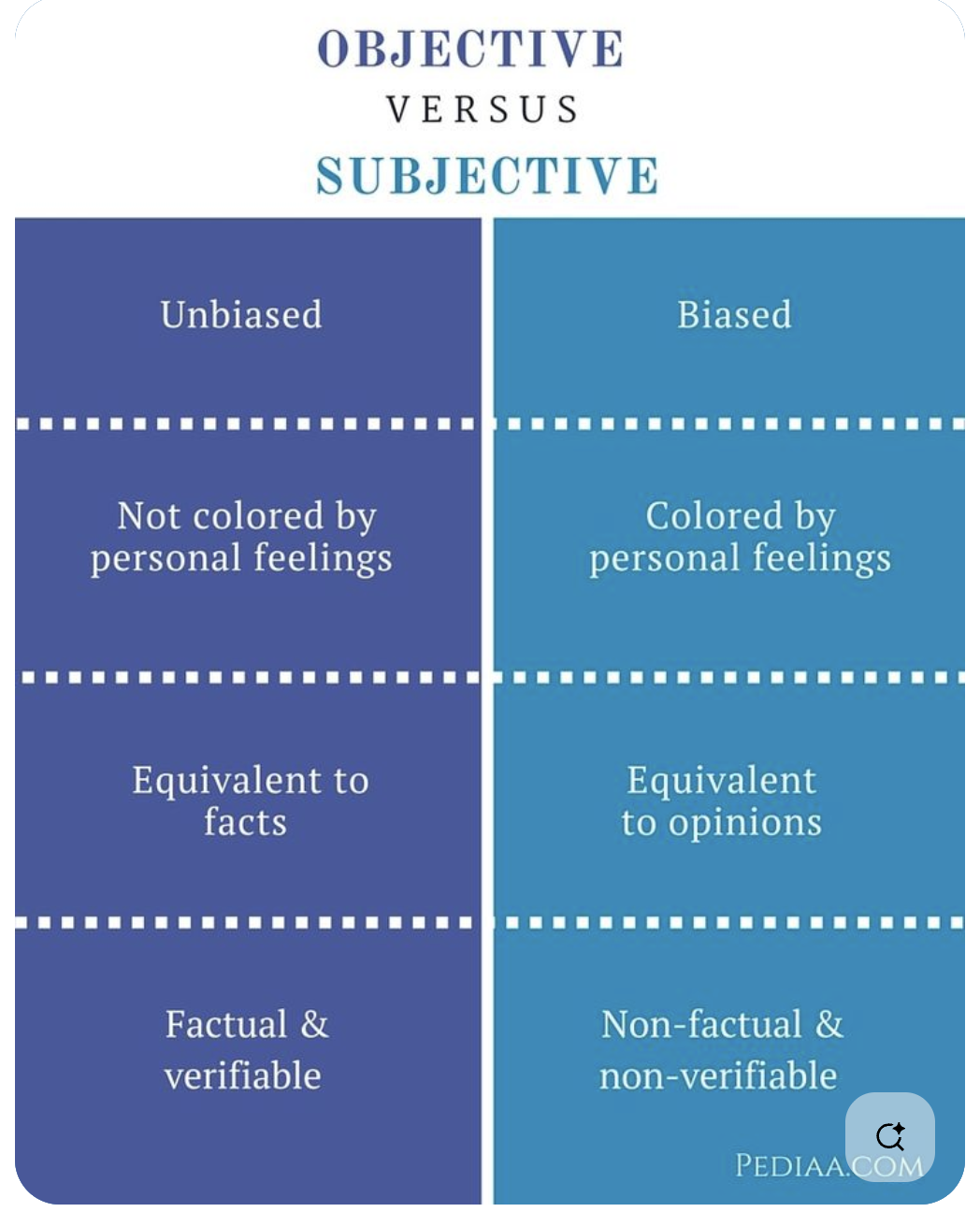

Subjective v. Objective

While by objective measures a majority of women going through the MT may not be “cognitively impaired,” the subjective experience of brain fog and cognitive decline can create profound discomfort, a “crisis of identity,” and “biographical disruption” that needs to be acknowledged and addressed.

Johnson & Ogden (2025) conducted a qualitative study that included both young women’s and older women’s subjective experiences of brain fog. It was the intent of the authors to look at how brain fog was experienced at either end of the reproductive spectrum. Some of their findings include:

· Daily disruptions in cognitive function in both groups that seemed to be triggered by hormonal fluctuations (natural or contraceptive) and exacerbated by sleep deprivation.

· A “cycle of impact” whereby the subjective effects of cognitive dysfunction triggered questions about their self-worth and capability; emotions of frustration, embarrassment, and anger took a toll on self-esteem; and all of these created a vicious cycle that aggravated brain fog symptoms.

· An overarching theme of “crisis of identity” in which the gap between who women had known themselves to be and how they now experienced themselves to be created a sense of loss, disruption, confusion, fear, frustration, and self-doubt. Anxiety and stress were triggered by fear of how others viewed them and how they imagined their behavior was perceived by peers, coworkers, and teachers.

Interestingly, some protective factors for working with brain fog emerged from this study.

Older women seemed to have an easier time reframing their experience, unpleasant as it may have been. The authors theorized that this may be due to a few factors:

· Older women have had more time to be themselves. They are more likely to be grounded in self-knowledge and more confident in their sense of themselves.

· In contrast to the younger women, many of whom experienced brain fog cyclically with different phases of their menstrual cycle or because they were taking hormonal contraception, the older women understood their brain fog to be contextualized within the menopause transition. They also understood the MT to be transient, and so they were able to understand that their symptoms were likely to be temporary.

· Access to the experiences of others was felt to be supportive and protective in going through the changes of perimenopause. One of the older women said, “I feel positive I will get through it because I have older friends that no longer have brain fog” (Johnson & Ogden, 2025, p.8).

· Although both the older and younger women used self-care in the form of prioritizing attention to sleep, diet, and exercise, the older women were “more likely to emphasise prioritizing themselves as their form of self care” (p.8).

Hormone Therapy & Brain Health

There are, as Maki & Jaff (2022) point out, “critical gaps in the data” about whether the cognitive dysfunction experienced in the perimenopausal period is predictive of dementia risk. Nor do we have clear, consistent data about how menopause hormone therapy (MHT) either supports or undermines brain health. Mosconi writes that “There hasn’t been a single clinical trial of hormone therapy for dementia prevention among women in perimenopause, which is simply unacceptable” (p.129).

The controversial study into hormone use during menopause, the Women’s Health Initiative, had an ancillary Memory Study arm (WHIMS). Although this study showed that there was an increase in risk of dementia with the use of hormone therapy, there are several caveats:

· The study was small and poorly designed.

· Participants were restricted to postmenopausal women 65 years of age or older.

o Many of these participants already had cardiovascular disease and, because of their age, may have already had neurological deterioration prior to study participation and hormone use. We don’t know because that wasn’t checked.

· The hormones used were equine estrogens and synthetic progestogens.

o Non-bio-identical hormones always carry a greater risk of disease burden.

It’s important to note that “reexaminations of the fewer younger women (those fifty to fifty-nine) included in the WHI provided important evidence that HRT started in midlife may indeed help reduce the risk of dementia” (Mosconi, p.129).

Other studies conducted in Finland and the UK have demonstrated conflicting findings that are further complicated by differing risks based on how many years one has been taking MHT.

While there is currently no scientific evidence that MHT will stop cognitive decline or improve brain fog symptoms, there is evidence that supplementing with estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone can improve sleep, relieve vasomotor symptoms, improve mood, and subjectively enhance cognitive functioning. Whether this is due to placebo effect or hormone replacement is unlikely to matter to a woman who feels as if she’s recovered her brain power and sense of self.

The complexity of women

Johnson & Ogden’s study of younger and older women who experience brain fog revealed how complex the hormonal workings of women’s bodies can be. The younger women experienced brain fog either with the natural hormonal fluctuations of their monthly cycle or by taking hormonal contraceptives that triggered symptoms of brain fog. However, older women were plunged into brain fog by the decline and absence of hormones and were able to alleviate their brain fog with hormonal supplementation. Clearly, not only the absence or presence of certain hormones, but the combinations and concentrations of hormones in relationship with each other, contribute to a sense of well-being or illness.

Both Gunter and Mosconi are clear in their understanding of menopause as a time when women’s brains undergo a natural process of rewiring. This neuroplasticity is present at pivotal points in women’s life cycles—puberty, pregnancy, and perimenopause. The pruning and laying down of new pathways help to prepare women for each new phase of life, but this reconstruction also tends to knock out the power in certain areas for a time and can shake the foundations of a woman’s sense of herself as she transforms.

Gunter also reminds us that societal and medical misogyny play a role in women’s misunderstanding of themselves and their complexity. Additionally, stigma attached to medical conditions that affect the brain can add to the shame that women may already feel about being “hormonal,” “old,” or “out of it.” Stereotypes about hormonal, aging women can lead providers to dismiss the symptoms and concerns of even those women who self-advocate. It’s critical that we stay aware of who we are and how we are being treated.

Putting it in Perspective

Here are some important things to understand about brain fog during the menopause transition (MT):

· The cognitive changes that are most common during the MT happen in the domains of verbal learning and memory, such as encoding and recall of words and other verbal material. (Maki & Jaff, 2022)

· There may also be some effects on psychomotor speed and working memory/attention. “Working memory refers to the ability to hold and manipulate items in short-term memory, such as keeping a new email address in mind while typing the subject of the email” (Maki & Jaff, 2022).

· Misplacing items, having difficulty concentrating, and being organizationally challenged are also common experiences during the MT, but do not necessarily translate into measurable cognitive or neurobiological changes.

· In many cases, what is subjectively felt by a person experiencing cognitive challenges she may call “brain fog,” does not reflect any objective cognitive deficits and cognitive functioning “re[mains] within normal limits” (Denno et al., 2025; Maki & Jaff, 2022).

· In fact, even when women are experiencing some measurable cognitive impairment during the MT, they continue to outperform men in those same cognitive domains. (Gunter, 2021; Mosconi, 2024).

· Across the board research has demonstrated that menopause related cognitive changes are temporary. Once a person has crossed over and spent a couple of years in postmenopause, their cognitive functioning tends to return to premenopausal levels as long as there is not an underlying disease process occurring.

· The onset of Alzheimer’s in women prior to the age of 65 is extremely rare unless there is a family history of early-onset Alzheimer’s.

· Even if one does have a genetic risk of developing Alzheimer’s or dementia, “it is estimated that about 40% of dementias worldwide are due to modifiable risk factors” including diet, physical and cognitive activity, smoking, social interaction, hypertension, diabetes, hearing impairment, mood disorders, air pollution, TBI, and alcohol intake (Maki & Jaff, 2022).

Although some of us may fear that our brains have started to disintegrate and we are starting to lose the thread, what we experience in perimenopause is analogous to the “mommy brain” that many women describe postnatally. Just as their brains have rewired to be focused on the needs and concerns of infant and child survival for a time, older women’s brains are being rewired to reorient us to our own needs and concerns in preparation for our next phase of life.

References

Denno, P., Zhao, S., Husain, M., & Hampshire, A. (2025). Defining brain fog across medical conditions. Trends in Neurosciences. https://www.cell.com/trends/neurosciences/fulltext/S0166-2236(25)00017-7

Gunter, J. (2021). The Menopause Manifesto. Citadel Press.

Johnson, H., & Ogden, J. (2025). Much more than a biological phenomenon: A qualitative study of women’s experiences of brain fog across their reproductive journey. Journal of health psychology, 30(8), 1963-1976. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053241290656

Maki, P. M., & Jaff, N. G. (2022). Brain fog in menopause: a health-care professional’s guide for decision-making and counseling on cognition. Climacteric, 25(6), 570-578. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2022.2122792

Metcalf, C. A., Johnson, R. L., Novick, A. M., Freeman, E. W., Sammel, M. D., Anthony, L. G., & Epperson, C. N. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences interact with inflammation and menopause transition stage to predict verbal memory in women. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity-Health, 20, 100411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2022.100411

Miller, V. M., Naftolin, F., Asthana, S., Black, D. M., Brinton, E. A., Budoff, M. J., ... & Harman, S. M. (2019). The Kronos early estrogen prevention study (KEEPS): what have we learned?. Menopause, 26(9), 1071-1084. DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001326

Mosconi, L. (2024). The Menopause Brain. Penguin Random House.

Spencer, C.J. (2025, July 29). Understanding brain fog in the menopause transition. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/understanding-brain-fog-menopause-transition-2025a1000jul

Images

Spider woman: https://www.girlmuseum.org/mythological-girls-spider-grandmother-22/

Subjective/Objective: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/difference-between-objective-and-subjective--391039180153348087/